Ahmed M. Al-Harby¹², Fatimah Al-salemi¹, Khalid Ngah², Sara Elsahmy¹, Nasser Y. Sofian²

Full Text

- Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic neurological disorders worldwide, affecting over 50 million people, with a significant proportion residing in Muslim-majority countries [1]. The burden of epilepsy in these regions is compounded by social stigma, limited access to neurologists, and challenges in medication adherence [2]. In countries such as Pakistan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, epilepsy prevalence ranges from 4 to 8 per 1000 individuals, with a substantial number of patients undergoing long-term antiepileptic therapy [3]. Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar, observed by Muslims globally as a period of spiritual reflection and fasting. During Ramadan, adult Muslims abstain from food, drink, and oral medications from dawn (Suhur) to sunset (Iftar) for 29 to 30 consecutive days [4]. This change in routine may significantly impact the pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), especially those with short half-lives or narrow therapeutic windows. Additionally, altered sleep patterns, dehydration, and potential hypoglycemia during prolonged fasting hours may further increase seizure susceptibility [5].

Despite these concerns, many patients with epilepsy choose to fast, often without adjusting their treatment regimens. The impact of Ramadan fasting on seizure frequency and control remains controversial, with some studies reporting increased seizure risk [6], while others suggest no significant adverse outcomes [7]. Given the widespread observance of Ramadan and the potential clinical implications for epilepsy management, it is essential to synthesize the existing evidence. This systematic review aims to evaluate the current literature on the relationship between Ramadan fasting and seizure control among patients with epilepsy. The findings will help guide clinicians in counseling and managing patients who wish to fast while maintaining optimal seizure control.

- Methods

- Search strategy and study selection

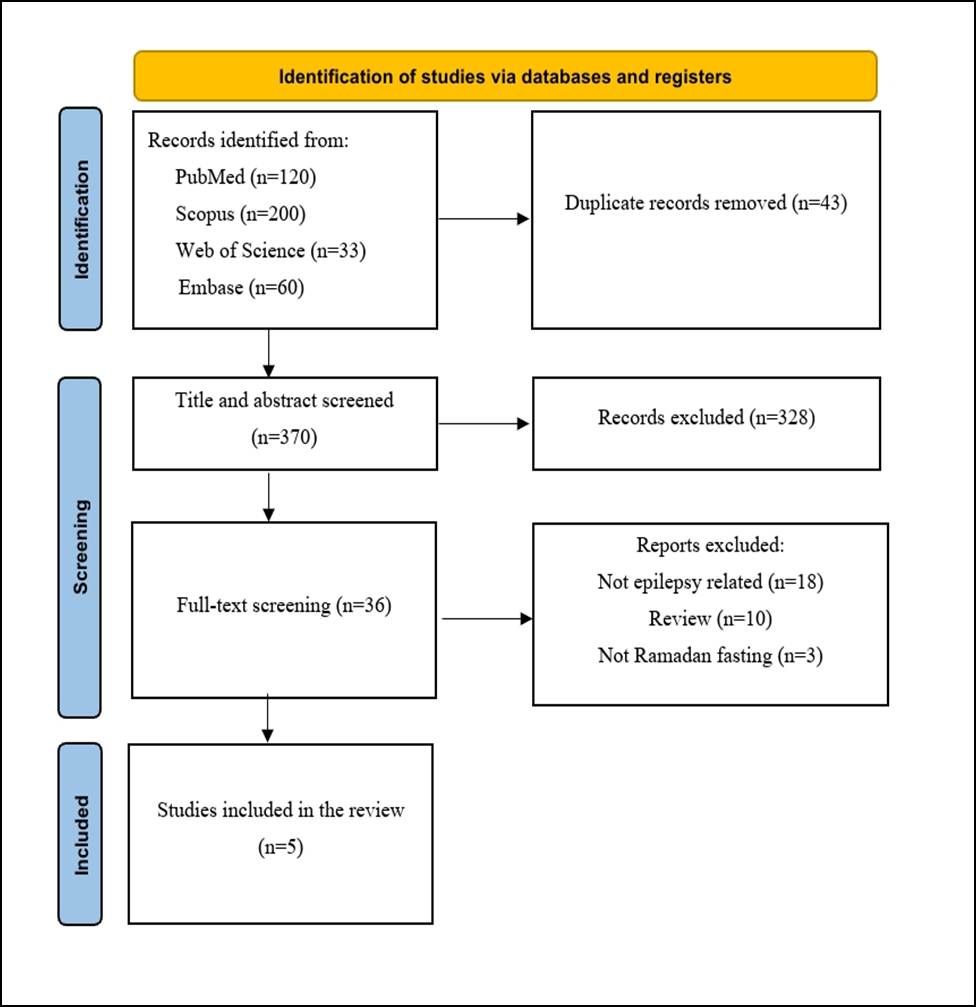

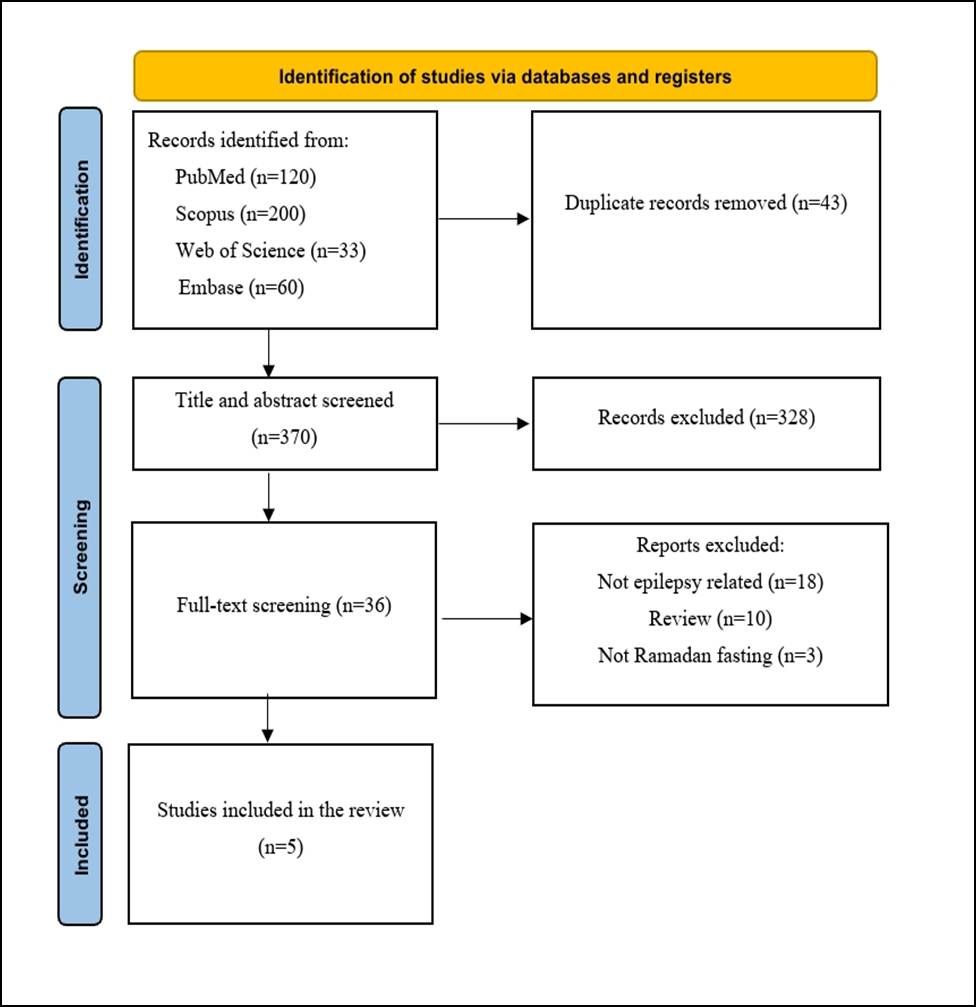

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [8]. We searched four databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science (WOS), and Scopus. The search was conducted on May 10, 2025. The search strategy used the following terms: (("Epilepsy" OR "Seizures") AND ("Ramadan" OR "Fasting") AND ("Seizure control" OR "Seizure frequency" OR "Antiepileptic drugs")). Each database was searched independently, and results were imported into EndNote for deduplication. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were assessed for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third reviewer.

- Eligibility criteria

This systematic review focuses on patients with epilepsy who observe Ramadan fasting, aiming to assess the impact of fasting on seizure frequency, seizure control, and medication adherence. The intervention of interest is Ramadan fasting, compared against non-fasting periods or non-fasting individuals with epilepsy. Eligible studies include observational designs such as cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies, as well as interventional studies, provided they are published in English. Exclusion criteria encompass animal studies, case reports, editorials, and non-peer-reviewed articles to ensure the inclusion of relevant, high-quality evidence.

- Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted into a standardized Excel sheet. Extracted variables included study design, country, population size, age range, seizure type, AED regimen, fasting details, seizure outcomes, and author conclusions. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies. Each study was assessed for selection, comparability, and outcome reporting. A narrative synthesis was performed due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcome reporting. Quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was not conducted.

- Results

- Search results

A total of 413 records were identified through database searching. After removing duplicates, 370 records remained for screening. Following title and abstract screening, 36 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 31 studies were excluded for the following reasons: no epilepsy-related outcomes (n = 18), review articles (n = 10), and not focusing on Ramadan fasting (n = 3). Ultimately, 5 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis [9-13]. The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

- Study characteristics and quality assessment

A total of five prospective observational studies were included in this review, comprising a cumulative sample of 672 patients with epilepsy who were evaluated before, during, and after the month of Ramadan. The key characteristics and findings of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

All included studies employed a prospective observational design and aimed to evaluate the effect of Ramadan fasting on seizure control, with some extending their scope to psycho-behavioral or quality of life outcomes. The largest study by Magdy et al. (2022) (n=321) investigated various seizure types and found significant reductions in focal and myoclonic seizures during Ramadan and Shawwal compared to Shaaban, while no significant changes were noted in generalized tonic-clonic seizures [9]. Similarly, another study by Magdy et al. (2025) on adolescents (n=120) demonstrated a significant reduction in focal and absence seizures, alongside improvements in aggression and impulsivity scores, though no changes in depressive symptoms were observed [11].

In contrast, Gomceli et al. (2008) reported a significant increase in seizure frequency during Ramadan, which was associated with alterations in antiepileptic drug regimens [12]. Meanwhile, Al-Qadi et al. (2020) found a 21% reduction in seizures during Ramadan and a 29% reduction post-Ramadan, without significant changes in quality-of-life scores [10]. The smallest study by Abd-Elmotalib et al. (2015) (n=80) showed no significant difference in seizure frequency between fasting and non-fasting patients, and found no correlations between seizure activity and sleep duration or prayer practices [13].

The methodological quality of the studies, as assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, ranged from moderate to high (6 to 9 stars). Three studies (Magdy 2022, Magdy 2025, and Al-Qadi 2020) scored 8–9 stars, indicating strong selection, comparability, and outcome assessment domains. The remaining two studies received lower scores due to limited comparability and less rigorous outcome measurements (Table 2).

- Discussion

This systematic review synthesized findings from five prospective observational studies investigating the impact of Ramadan fasting on seizure frequency, seizure control, and medication adherence among patients with epilepsy. Our analysis highlights the complex and often individualized effects of fasting on epilepsy management, influenced by metabolic changes, medication regimens, and behavioral factors. While some evidence suggests potential improvements in seizure control related to metabolic adaptations and enhanced medication adherence during Ramadan, other studies report increased seizure risk, particularly linked to medication adjustments and sleep disturbances. These divergent findings underscore the need for personalized clinical approaches and further research to optimize care for fasting patients with epilepsy.

Ramadan fasting induces profound physiological and behavioral changes that have complex effects on people with epilepsy (PWE). The metabolic shift during fasting, characterized by increased reliance on fatty acids and ketone bodies instead of glucose, can influence neuronal excitability and seizure threshold. This metabolic adaptation resembles some effects of ketogenic diets known for their anticonvulsant properties, potentially contributing to improved seizure control observed in some PWE during Ramadan [14,15].

Ramadan fasting induces profound physiological and behavioral changes that have complex effects on people with epilepsy (PWE). The metabolic shift during fasting, characterized by increased reliance on fatty acids and ketone bodies instead of glucose, can influence neuronal excitability and seizure threshold. This metabolic adaptation resembles some effects of ketogenic diets known for their anticonvulsant properties, potentially contributing to improved seizure control observed in some PWE during Ramadan [14,15]. However, fasting may also provoke adverse metabolic disturbances, such as hypoglycemia and electrolyte imbalances, which are well-established seizure triggers, especially in patients with poorly controlled epilepsy [14,16]. These findings underscore the need for close metabolic monitoring during fasting periods.

Medication adherence remains a critical factor influencing seizure control during Ramadan. Alterations in meal timing disrupt usual antiepileptic drug (ASM) dosing schedules, risking subtherapeutic drug levels and breakthrough seizures. Careful adjustment of medication regimens, such as consolidating doses to coincide with pre-dawn (Suhoor) and post-sunset (Iftar) meals, can help maintain effective drug concentrations, as demonstrated with carbamazepine [14,17]. Pre-Ramadan counseling and individualized management plans are essential to support adherence and avoid inadvertent dose omissions. Notably, some studies have documented improved medication adherence during Ramadan, possibly related to more structured daily routines and reduced external commitments, which may paradoxically contribute to better seizure control for certain patients [15].

Regarding seizure frequency, the evidence is heterogeneous. Some reports indicate an increased seizure risk during fasting, particularly in patients with recent medication changes or sleep deprivation [18,19]. Conversely, other studies have documented a reduction in focal and myoclonic seizures during Ramadan, potentially reflecting the beneficial metabolic effects of fasting and improved medication adherence [20]. This variability highlights that the impact of fasting is highly individualized and influenced by baseline seizure control, epilepsy type, and lifestyle factors, including sleep quality. Sleep disruption caused by altered Ramadan schedules remains a recognized seizure precipitant, emphasizing the importance of maintaining good sleep hygiene during fasting periods [14,19].

Quality of life (QoL) considerations extend beyond seizure frequency. Despite some improvements in seizure control, QoL measures may not improve during Ramadan due to fatigue, dehydration, sleep disturbances, and psychosocial stress related to managing epilepsy within religious and cultural frameworks [21,22]. Patients often face internal conflicts between religious obligations and medical advice, sometimes leading to anxiety or guilt, which may further impact well-being. Culturally sensitive patient education and collaboration with religious authorities can help reconcile these tensions, facilitating safer fasting practices without compromising spiritual needs [23].

Clinical management guidelines emphasize individualized care, pre-Ramadan assessments, and patient education to optimize outcomes. Health providers should assess seizure stability, ASM regimens, metabolic status, and psychosocial factors before fasting commences. Regular monitoring during Ramadan is advised to detect early warning signs of metabolic imbalance or seizure exacerbation [14]. Encouraging hydration and nutritional adequacy during non-fasting hours, maintaining consistent medication schedules, and supporting sleep hygiene are practical strategies to mitigate risks. Collaboration between healthcare providers, patients, and religious leaders can enhance adherence and reduce psychosocial burdens associated with fasting [23].

Conclusion

In conclusion, while Ramadan fasting can be safe for many PWE with well-controlled epilepsy and stable ASM regimens, it requires careful individualized planning and monitoring. The interplay of metabolic, pharmacological, and psychosocial factors during fasting necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to optimize seizure control and quality of life. Further prospective studies with larger cohorts are needed to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of fasting-related changes in epilepsy and to refine clinical guidelines that balance religious practices with patient safety.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Funding: None.

Acknowledgements: None.

Author Contributions: A.M.A.-H. conceived and designed the study. F.A.-S. and S.E. collected the data and conducted the literature review. K.N. and N.Y.S. performed the data analysis and interpretation. A.M.A.-H. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to revising the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Table 1. Summary of the included studies.

Study ID | Sample (n) | Study design | Study question | Main findings |

Magdy 2022 | 321 | Prospective observational | Does Ramadan fasting affect the frequency of different seizure types in patients with active epilepsy? |

| Focal and myoclonic seizures were significantly improved in the months of Ramadan and Shawaal compared to Shaaban. However, absence seizures were significantly improved only in Ramadan compared with Shaaban. The frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures did not significantly differ between the three months. |

Al-Qadi 2020 | 37 | Prospective observational | What is the effect of Ramadan fasting on seizure control and quality of life in epilepsy patients? | Seizures declined by 21% during Ramadan (adjusted coefficient = 0.79, p < 0.01) and by 29% post-Ramadan (adjusted coefficient = 0.71, p < 0.01); quality of life scores showed no significant change. |

Magdy 2025 | 120 | Prospective observational | What is the effect of Ramadan fasting on seizure frequency and psycho-behavioral outcomes in adolescents with epilepsy? |

| Significant reduction in focal seizures (p=0.009) and absence seizures (p=0.027) during Ramadan; aggression and impulsivity scores decreased (MOAS p=0.003; BIS-11-SF p=0.005); no significant change in depression scores (PHQ-9). |

Gomceli 2008 | 114 | Prospective observational | How does Ramadan fasting affect seizure frequency and drug regimen alterations in patients with epilepsy? |

| Significant increase in seizure frequency during Ramadan (p < 0.001); increased seizure risk linked to changes in drug regimens (p < 0.05); no difference between mono- and polytherapy groups. |

Abd-Elmotalib 2015 | 80 | Prospective observational | Does fasting and Ramadan-related activities affect seizure frequency in epileptic patients? |

| No significant change in seizure frequency related to fasting status (P=0.625); higher seizure incidence in non-fasting group; no significant correlations with sleep duration or prayer adherence; fasting and Ramadan activities did not adversely affect seizures. |

Abbreviations: MOAS: Modified Overt Aggression Scale, BIS-11-SF: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Short Form, and PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Table 2. Quality assessment by NOS.

Study ID | Selection (max 4★) | Comparability (max 2★) | Outcome (max 3★) | Total (max 9★) |

Magdy 2022 | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

Al-Qadi 2020 | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★☆ | 8★ |

Magdy 2025 | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

Gomceli 2008 | ★★★ | ★☆ | ★★☆ | 7★ |

Abd-Elmotalib 2015 | ★★★ | ★☆ | ★★ | 6★ |

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart.