Mapping the Burden of Restless Legs Syndrome across Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Hyder Mirghani¹, Osama Hamdi Asiri², Khaled Abdulrahman Alshehri², Maitha MohammedAlthawy³, Amnah Ali Alharbi⁴, Maryam Mohammed Abdulaal⁴, Munia Ghassan Alqahtany⁵, WahbiIbrahim Alnazawi⁶, Dhuha Abduallah Alhuthaily⁷, Raghad Shami Alsharidi⁸, Shroog Ibrahim AlQurashi⁹, Abdulaziz Jameel AlOtaibi¹⁰, Abdulmajeed Albalawi¹¹

Full Text

1. Introduction

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) is a common neurologic sensorimotor disorder characterized by unpleasant sensation and an urge to move the legs that, with worsening during rest [1]. It is associated with impaired sleep disturbance, daytime malfunctioning, and reduced quality of life [2]. The prevalence of RLS varies worldwide, being around 5% to 15% [3]. Several factors have been linked to RLS, echoing a constellation of neurological, genetic, and metabolic factors. Disturbance in the dopaminergic pathways and the malfunction in iron metabolism within the nervous system, especially the substantia nigra and basal ganglia, were postulated as pathophysiological mechanisms [4]. Some genetic loci, like MEIS1, BTBD9, and MAP2K5, have been pointed out as possible determining factors for primary RLS [5]. On the other hand, secondary RLS may sometimes be related to conditions like chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, multiple sclerosis, and iron deficiency anemia [1].

Management includes treatment of secondary causes, lifestyle modification, and pharmacologic treatment with dopaminergic agents, treatment and the identification of RLS in its gabapentin, or opioids in refractory cases [6]. The early stages are essential in order to lessen the related morbidity and to upgrade the quality of life of the patients. RLS still remains tremendously burdensome and has considerable adverse effects on sleep, mood, and cardiovascular health, nevertheless it is still underdiagnosed and an undertreated condition [7]. In Saudi Arabia, awareness and screening for RLS remain limited [8]. Previous studies have demonstrated variable prevalence rates in different subgroups of patients, such as community-based samples and high-risk patient groups. Nevertheless, the overall national prevalence has not been determined yet through a meta-analysis. Given the clinical significance of RLS and the heterogeneity among local studies, a systematic review of the literature is warranted. Estimating the pooled prevalence of RLS in the Saudi population will help identify high-risk groups, guide future research, and inform public health and clinical efforts to improve diagnosis and management. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aim to estimate the pooled prevalence of RLS among adults in Saudi Arabia.

2. Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted between August and October 2025 in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, with the aim of estimating the pooled prevalence of RLS among adults in Saudi Arabia [9].

3. Selection criteria

We included studies that investigated adults aged 16 years or older living in Saudi Arabia, regardless of nationality, and conducted in community, primary care, or hospital settings. Eligible studies were observational in design, including cross-sectional, cohort, case-control, or population-based studies, and reported the prevalence of RLS. Diagnosis had to be based on recognized clinical standards, such as the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) criteria, or a validated screening instrument. No restrictions were applied regarding publication year. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on children or adolescents (<16 years), were conducted outside Saudi Arabia, or did not provide prevalence data (e.g., case reports, case series, reviews, or editorials). We also excluded conference abstracts lacking full data and other publications irrelevant to the study objectives.

4. Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across four major electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and Ovid. No restrictions were applied regarding the year of publication, but the search was limited to studies published in the English language. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to RLS and Saudi Arabia, using appropriate Boolean operators. The full search string was as follows: ("Restless Legs Syndrome"[MeSH Terms] OR "restless legs syndrome"[tiab] OR "Restless Legs Syndrome"[tiab] OR "restless legs"[tiab] OR RLS[tiab] OR "Willis-Ekbom"[tiab] OR "Willis Ekbom"[tiab] OR "Willis Ekbom disease"[tiab] OR WED[tiab]) AND ("Saudi Arabia"[MeSH Terms] OR "Saudi Arabia"[tiab] OR Saudi[tiab] OR "Saudi Arabian"[tiab] OR "Kingdom of Saudi Arabia"[tiab] OR KSA[tiab]). All retrieved records were imported into Rayyan for reference management, deduplication, and independent screening by reviewers. Two reviewers independently screened all records using Rayyan. Titles and abstracts were checked against the eligibility criteria, and any studies that appeared relevant or where there was uncertainty were moved to full-text review. Differences in judgment were discussed between reviewers, and when agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer provided a final decision. The reasons for excluding full-text articles were documented.

5. Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from each included study were extracted independently by the reviewers using a structured Excel spreadsheet designed for this review. Extracted details included: the first author, year of publication, study design, study population, setting or region, diagnostic tool or criteria used, number of RLS cases, total sample size, reported prevalence, and any subgroup data (such as by sex or comorbid conditions). All entries were cross-checked to ensure accuracy, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The methodological quality of the included studies was rated using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) quality assessment tool for cross-sectional and casecontrol studies [10]. It consists of 14 criteria, all of which assess potential sources of bias. Two investigators independently rated each study, and if any disagreement occurred, they discussed it mutually to reach consensus. The quality of included studies was rated either good, fair, or poor, and this quality rating was taken into account when interpreting the pooled findings

6. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using a random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird method) to account for between-study variability. The pooled prevalence of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) was calculated along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Prevalence estimates were transformed using the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine method to stabilize variances before pooling, and the results were subsequently back-transformed for interpretation. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic and quantified by the I² index, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on population type (general population, clinical patients, students, and pregnant women) and diagnostic criteria (IRLSSG versus other tools) to explore potential sources of variability. Sensitivity analysis was performed using a leave-one-out approach, where each study was sequentially excluded to examine its influence on the pooled estimate. Potential publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots and statistically using Egger’s regression test. All statistical analyses were performed using StatsDirect software and R software employing the meta and metafor packages.

7. Results

Search results

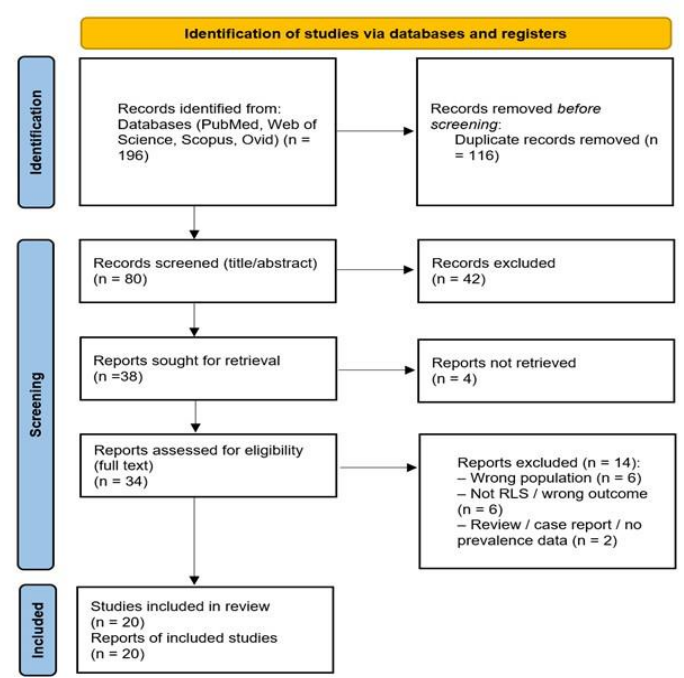

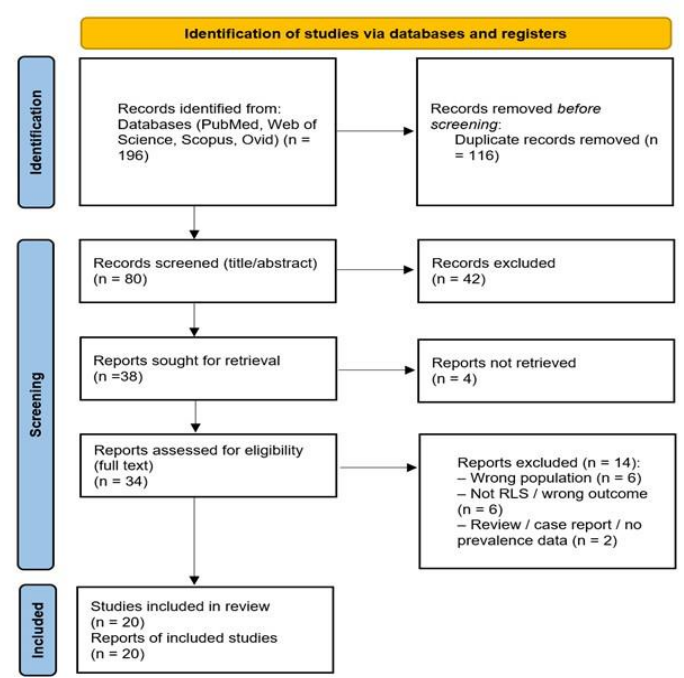

Our database search initially yielded 196 records. After removing 116 duplicates, 80 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Following this step, 42 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 38 articles were selected for fulltext review, though 4 could not be accessed in full despite attempts to retrieve them. After detailed evaluation of the 34 available full-text papers, 14 were excluded—mostly because they did not specifically assess RLS, or lacked sufficient data for analysis. In the end, 20 studies satisfied all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the meta-analysis [8,11–29]. The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The PRISMA flowchart.

8. Characteristics of included studies

A total of 20 observational studies encompassing 22,383 participants were included in this metaanalysis. The studies represented all major regions of Saudi Arabia, with the Central (Riyadh) and Western (Jeddah, Makkah) regions most frequently studied, followed by contributions from the Southern (Albaha) and Northern (Tabuk) provinces. Most studies employed a cross-sectional design (n = 17), with a few adopting case–control (n = 2) or prospective cross-sectional (n = 1) designs. The sample sizes varied widely, ranging from 44 to 10,106 participants. The majority of studies assessed the general adult population (n = 17322), while others investigated specific clinical or demographic subgroups including patients on dialysis, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and sickle cell disease (n ≈ 1,732), as well as pregnant women (n ≈ 1,718) and university students (n ≈ 1,611). Diagnosis of RLS was primarily established using the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) diagnostic criteria, which were applied in 17 studies. The remaining studies used alternative or screening tools, including the Sleep-50 questionnaire, RLS screening questionnaire, or self-reported assessments. Both male and female participants were represented, although several cohorts focused exclusively on female populations, particularly those involving pregnancy or women’s health. A comprehensive overview of the included studies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. An overview of the included studies.

Study ID | Study design | Study population | Region (City/Area) or setting | Gender | Diagnosis of RLS |

Al-Jahdali, 2012 | Cross-sectional study | Patients on dialysis | Riyadh – two dialysis centers | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Younis, 2023 | Cross-sectional study | Patients with Multiple Sclerosis | King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, Jeddah | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Mirghani, 2021 | Case-control study (hospital-based) | Diabetic patients (cases) | King Fahad Specialist Hospital and primary healthcare centers, Tabuk City | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Alhejaili, 2024 | Cross-sectional study | Residents of nursing homes (geriatric and non-geriatric) | Six nursing homes in Jeddah | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Alnaaim et al., 2023 | Cross-sectional study | Saudi pregnant women | All provinces of Saudi Arabia | Female | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

BaHammam, 2011 | Cross-sectional study | General adult population | Primary healthcare centers in Riyadh, Makkah, and Albaha | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Alghamdi, 2025 | Cross-sectional study | Undergraduate students with sleep disorders | University settings, Saudi Arabia | Both | Restless Legs Syndrome Rating |

Aljohara, 2020 | Cross-sectional case-control study | Saudi pregnant women | King Saud University Medical City (KSUMC), Riyadh | Female | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Almeneessier, 2020 | Cross-sectional study | General adult female population | Primary care centers, Female University campus, King Saud University, Riyadh | Female | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

AlHarbi, 2021 | Prospective cross-sectional | Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Six hospitals in Central, Southern, and Western Saudi Arabia | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Alabdulgader, 2025 | Cross-sectional study | Medical students in Saudi Arabia | All regions of Saudi Arabia | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Goweda, 2021 | Cross-sectional study | Medical students | Faculty of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah | Both | Sleep-50 questionnaire for RLS |

Mosli, 2020 | Case-control study | Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah | Both | RLS screening questionnaire |

Khan, 2018 | Cross-sectional study | Pregnant Saudi women | Obstetric clinics at King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh | Female | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Sherbin, 2017 | Cross-sectional study | General adult population | King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

AlShareef, 2023 | Cross-sectional study | General adult population | Nationwide, Saudi Arabia (all 13 provinces) | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Alomri, 2024 | Cross-sectional study | Undergraduate university students in Saudi Arabia | Online survey | Both | Self-reported |

Wali, 2015 | Cross-sectional study | Patients on dialysis | Jeddah – three major hemodialysis centers | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Wali, 2015* | Cross-sectional study | General adult population | Jeddah – western region (four districts: south, east, northwest, central) | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

Wali, 2017 | Cross-sectional study | Patients with sickle cell disease | King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah | Both | IRLSSG diagnostic criteria |

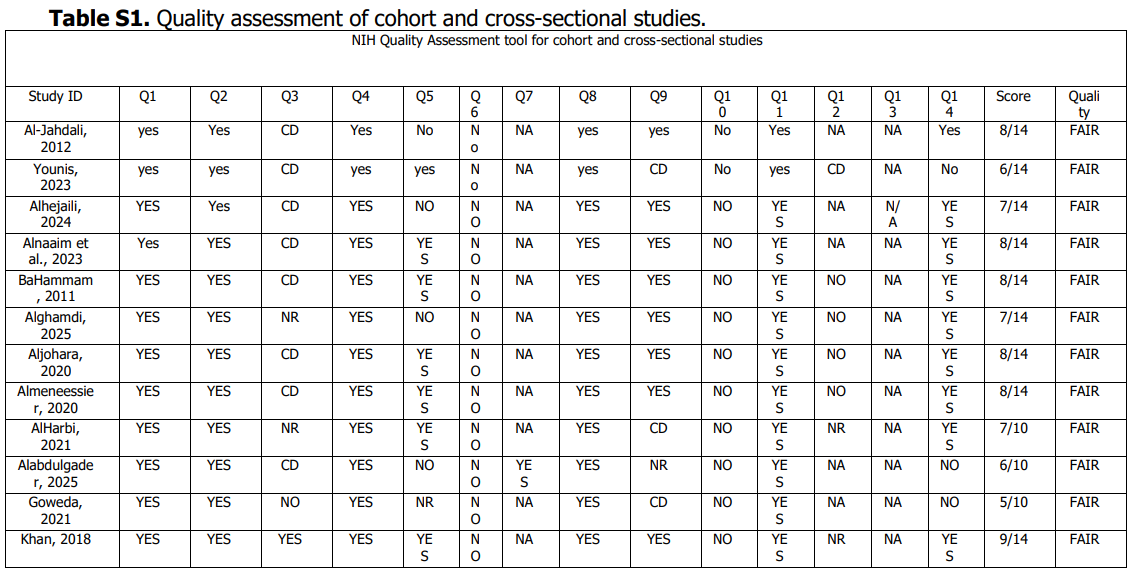

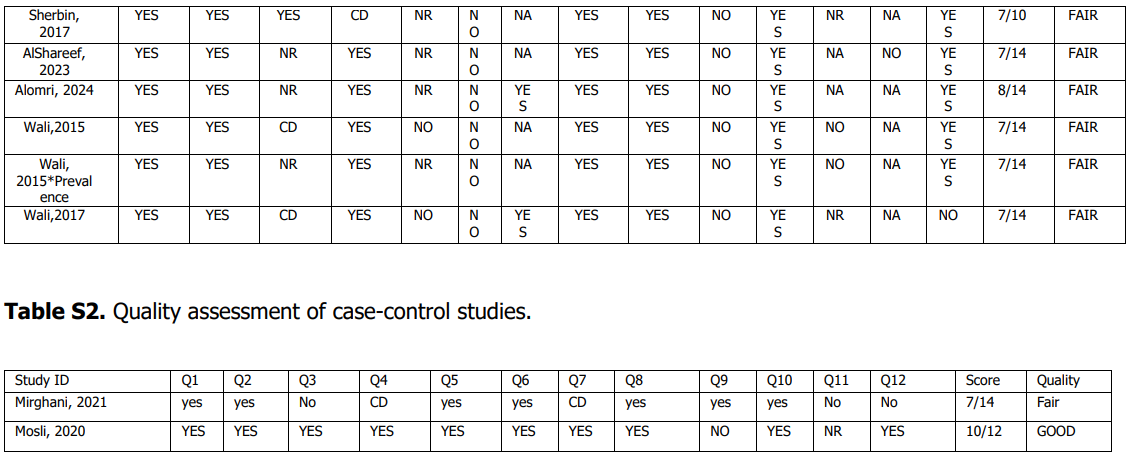

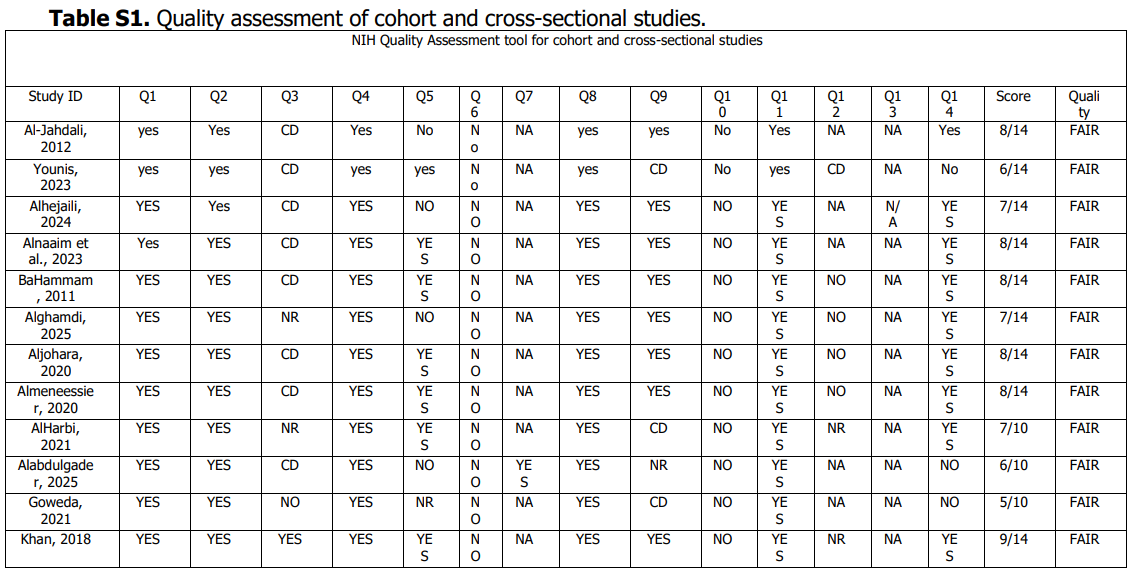

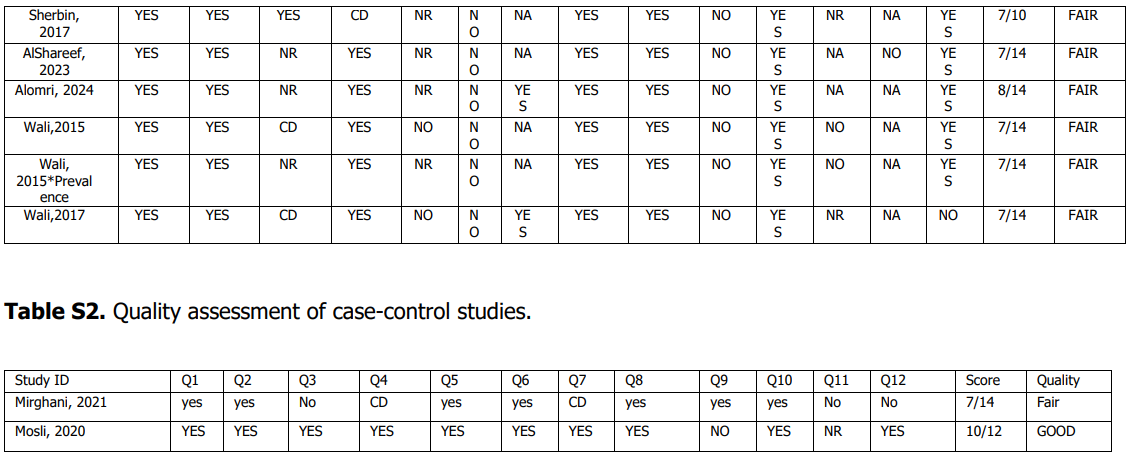

9. Quality assessment

The majority of studies (19 /20) were rated as fair quality, while one were rated as good quality. No study was classified as poor. Overall, most studies fulfilled several key methodological domains. The detailed assessment of each domain for individual studies is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

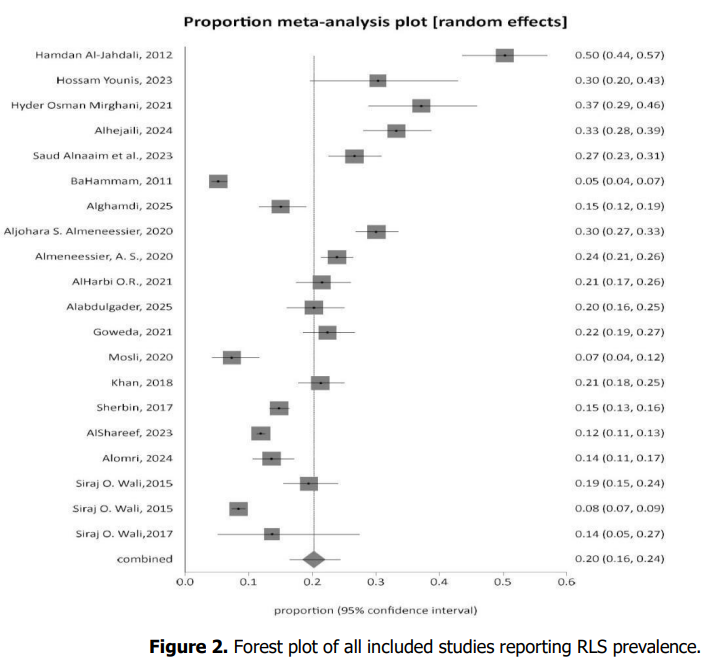

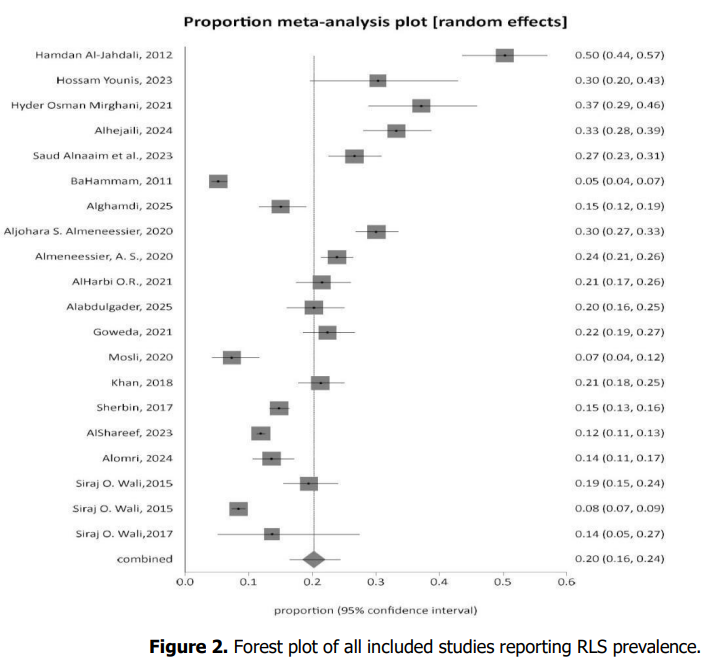

10. Overall pooled prevalence of RLS

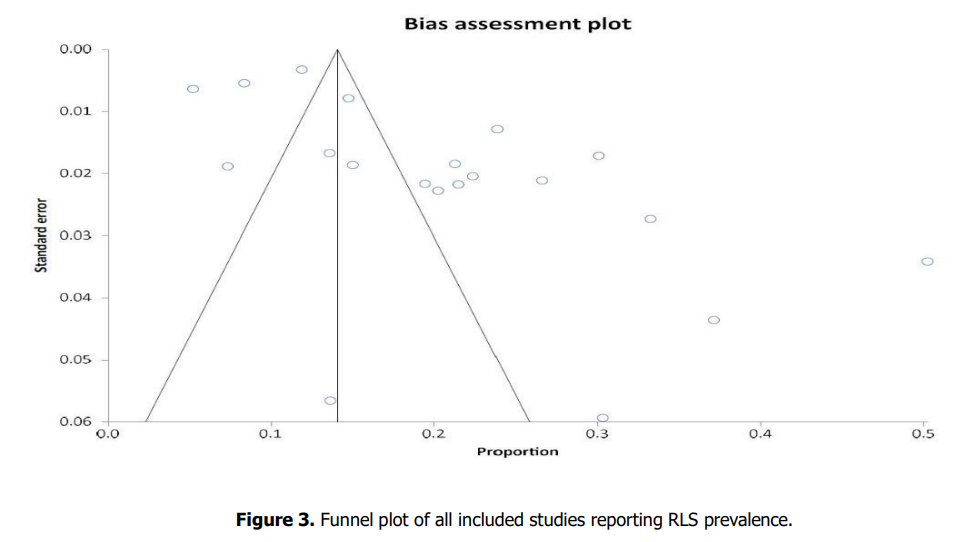

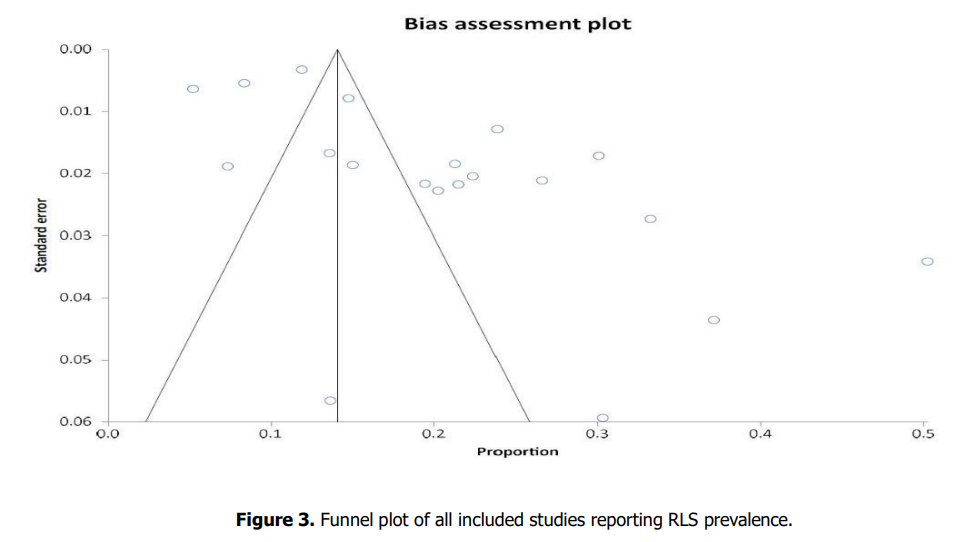

In this meta-analysis of 20 studies, the pooled prevalence of restless legs syndrome was 20.23% (95% CI, 16.40–24.36%) using a DerSimonian–Laird random-effects model (Figure 2). Between-study variability was (Cochran’s Q = 832.77; df = 19; p < 0.0001), with I² = 97.7% (95% CI, 97.4–98.0%) and a moment-based τ² of 0.047635. The funnel plot is presented in Figure 3. Publication-bias tests was Egger’s regression bias = 6.01 (95% CI, 2.70–9.31; p = 0.0013).

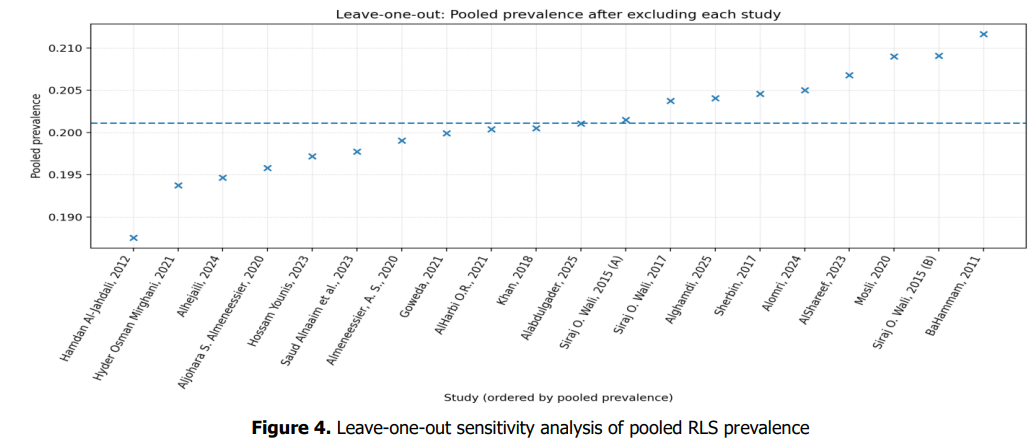

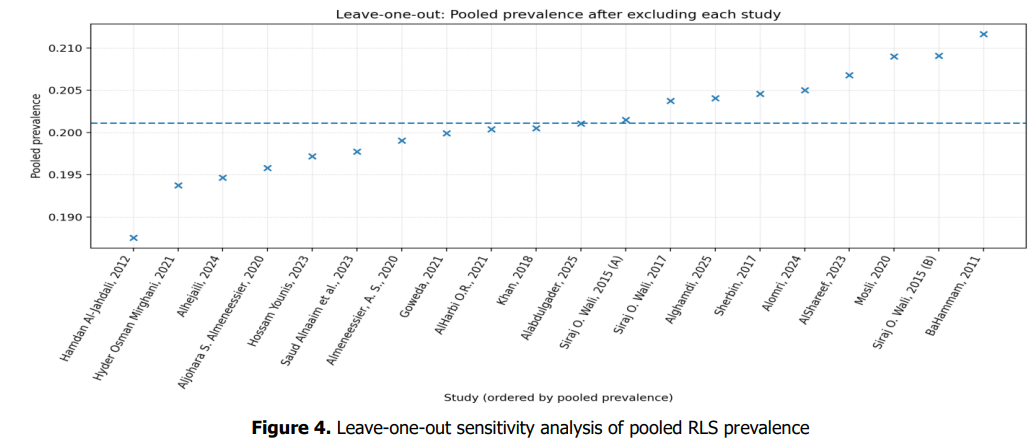

11. Sensitivity Analysis

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed to assess how individual studies affected the overall pooled prevalence (Figure 4). The baseline pooled prevalence of RLS was 20.23% (95% CI: 16.40– 24.36%), with a baseline heterogeneity of I² = 97.7%. When each study was excluded in turn, the overall estimate remained largely unchanged, varying only between 18.8% and 21.2%. The lowest pooled value occurred after removing Hamdan Al-Jahdali et al. (2012), which reduced the prevalence to 18.8%. The highest value was obtained when BaHammam (2011) was omitted, slightly increasing the estimate to 21.2%. Throughout all iterations, the heterogeneity level stayed relatively stable (I² = 97.4– 97.8%), suggesting that no single study had a dominant effect on the overall findings.

12. Subgroup analyses

In the general population (five studies; n = 17,322), the pooled prevalence of RLS was 12.13% (95% CI: 8.13–16.79%) under a random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird). Heterogeneity was high (I² = 98.3%, 95% CI: 97.8–98.7%; Cochran’s Q = 241.68, df = 4, p < 0.0001). No publication bias was detected (Egger’s test p = 0.64).

Among patients with clinical conditions (eight studies; n = 1,732), the pooled prevalence of RLS was 25.64% (95% CI: 16.44–36.07%) under a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 95.3%, 95% CI: 93.3– 96.5%; Cochran’s Q = 148.49, df = 7, p < 0.0001). No significant publication bias was observed (Egger’s test p = 0.19).

Among student populations (four studies; n = 1,611), the pooled prevalence of RLS was 17.63% (95% CI: 13.63–22.03%) under a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was considerable (I² = 80.2%, 95% CI: 18.3– 90.7%; Cochran’s Q = 15.13, df = 3, p = 0.0017). In pregnant women (three studies; n = 1,718), the pooled prevalence was 25.96% (95% CI: 20.92–31.33%) under a random. Effect effects model. Heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 83.8%, 95% CI: 9.3–92.9%; Cochran’s Q = 12.31, df = 2, p = 0.0021). When restricted to studies applying the IRLSSG diagnostic criteria (16 studies; n = 20,885), the pooled prevalence was 21.75% (95% CI: 17.15– 26.71%). Heterogeneity remained considerable (I² = 98.1%, 95% CI: 97.8–98.4%; Cochran’s Q = 801.40, df = 15, p < 0.0001). All subgroup findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Pooled prevalence of RLS across population subgroups in Saudi Arabian

Subgroups | RLS prevalence% | (95% CI) % | I2; P-value |

General population (5 studies) | 12% | (8–17) | I² = 98.3%; p < 0.0001 |

High risk groups (Elderly, DM, MS, ESRD, IBD, SCD) | 26% | (16–36) | I² = 95.3%; p < 0.0001 |

Pregnant females (3 studies) | 26% | (21–31) | I² = 83.8%; p = 0.002 |

Students (4 studies) | 18% | (14–22) | I² = 80.2%; p = 0.0017 |

Excluding studies not using IRLSSG diagnostic criteria (16 studies) | 22% | (17–27) | I² = 98.1%; p < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: Restless Legs Syndrome; Confidence Interval; I² = Measure of heterogeneity; Diabetes Mellitus; Multiple Sclerosis; End-Stage Renal Disease; Inflammatory Bowel Disease; Sickle Cell Disease; International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group.

13. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized data from 20 observational studies involving more than 22,000 participants to estimate the pooled prevalence of RLS among adults in Saudi Arabia. The estimated pooled prevalence of RLS was found to be 20.2%, which is significantly above the global average of about 5-15% as reported in Western nations [30]. This finding highlights that RLS constitutes a major but underrecognized health problem in Saudi Arabia. Such a high percentage indicates that one out of five adults in Saudi Arabia might have symptoms that correspond to RLS.

The high prevalence is very likely due to the combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors as well as the high incidence of metabolic and nutritional disorders in the area. Iron deficiency anemia, diabetes, vitamin D deficiency, chronic kidney disease, and pregnancy, among others, are conditions that are commonly seen in Saudi Arabia, and these are well-known secondary causes or RLS exacerbating factors [31–34] .

Despite the high pooled prevalence, heterogeneity was considerable, indicating wide variation across studies. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that no single study disproportionately influenced the pooled estimate, suggesting that variability stemmed from population and methodological differences rather than outliers. Subgroup analyses revealed important epidemiological patterns. The prevalence among the general population was 12%, aligning with international estimates but still at the upper end of global ranges. However, markedly higher rates were found in clinical and vulnerable populations; 26% among patients with chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, multiple sclerosis, end-stage renal disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and sickle cell disease) and 26% among pregnant women. These subgroups represent key targets for early recognition and management.

Among students, the prevalence of RLS was 18 %, which is particularly noteworthy considering their younger age and relative lack of major comorbidities. Lifestyle-related factors—such as irregular sleep patterns, academic stress, caffeine consumption, and smoking—may partly explain this prevalence in a student population. For example, one of the included study reported that students who consumed 3-4 cups of coffee daily had higher RLS occurrence compared to those who did not (42.9 % vs 18.6 %) [8].

Similarly, the significant prevalence among pregnant women is quite alarming, also being in the upper margin of global figures [35]. According to Almeneessier et al. (2020), RLS during pregnancy was found to be related to anemia, diabetes mellitus, vitamin D deficiency, and smoking which are all very common issues amongst women of childbearing age in Saudi Arabia [19]. In addition, another study by the same author, done on a large group of non-pregnant Saudi women (n = 1,136), revealed that RLS was present in 24% of cases, with vitamin D deficiency (OR 2.15) and diabetes mellitus (OR 4.41) identified as powerful predictors [20] .

The findings taken together clearly point out that metabolic and nutritional disturbances are actively involved in the development of RLS in Saudi women. The high incidence of RLS during pregnancy is a particularly worrying issue since it has been associated with sleeping problems, mood changes, and negative obstetric outcomes, therefore requiring more clinical attention and screening during prenatal care [36] .

The higher prevalence of RLS among patients with chronic illnesses likely reflects shared mechanisms involving systemic inflammation, iron dysregulation, and neuropathic injury. In DM, peripheral and small-fiber neuropathy may alter somatosensory input and disrupt dopaminergic signaling, predisposing to RLS [37] . In CKD, uremic toxins, metabolic derangements, and anemia impair central dopaminergic pathways and iron homeostasis [38]. Similarly, inflammatory bowel disease and sickle cell disease cause chronic inflammation and iron deficiency through blood loss, malabsorption, or hemolysis, leading to brain iron depletion, a key factor in RLS pathophysiology [39]. Similarly, in inflammatory bowel disease, mucosal inflammation, impaired intestinal iron absorption, and chronic cytokine activation (e.g., IL-6– mediated hepcidin upregulation) deficiency, lead to functional iron deficiency, dopaminergic dysfunction, and secondary RLS symptoms [21,22] .

In multiple sclerosis, demyelination within spinal and subcortical pathways interferes with sensorimotor integration and dopaminergic neurotransmission, leading to secondary RLS [13]. Collectively, these mechanisms explain the elevated RLS burden in these patient populations and highlight the importance of identifying and correcting reversible factors such as iron deficiency and systemic inflammation to mitigate symptom severity.

The considerable heterogeneity that was noted even after subgrouping most likely indicates differences in the diagnostic criteria, the methods of sampling, and the populations in the studies. While the majority of the research employed the standardized IRLSSG guidelines, some other studies depended on selfadministered questionnaires or unvalidated screening tools which might have either exaggerated or underestimated the prevalence. The differences in the geographical area within Saudi Arabia, the sex ratio, and the involvement of high-risk hospital-based patients also play a part in the inconsistency. In addition, cultural contrasts in the perception and reporting of symptoms could affect the diagnosis.

The review clearly shows that the high burden of RLS has very important consequences for both the clinical and the society domains. Despite its prevalence, RLS remains underdiagnosed and undertreated both globally and locally. Studies in Saudi Arabia indicate that most affected individuals have never been formally diagnosed or treated [11]. This underdiagnosis is mainly due to the lack of awareness of the problem from the sides of both health care providers and the public, also to the confusion by the similarity of the symptoms of RLS with those of insomnia, neuropathy, or musculoskeletal complaints. Given that RLS has a negative impact not only on sleep quality but also on mood, productivity, and cardiovascular health, it is necessary to conduct regular screening and provide prompt treatment for the condition, particularly for such populations at risk as pregnant women, patients with diabetes or renal diseases, and those with unexplained sleep complaints. The adoption of standardized screening practices in primary care and obstetrical clinics would promote timely detection and treatment.

14.Strengths and limitations

This meta-analysis is the first to look in-depth the prevalence of RLS in Saudi Arabia and to give a national picture of the different subpopulations. It demonstrates the disease's considerable burden and the urgent need for more acknowledgment of it in clinical practice. The results can be utilized in healthcare setup, disease awareness campaigns, and even in research that will investigate RLS risk factors and treatment in the Saudi context. Nevertheless, the study has several limitations, which must be recognized. The high degree of heterogeneity between studies limits the accuracy of pooled estimates. Causal inference was limited by the fact that a number of studies were cross-sectional. The use of different diagnostic tools and methods of sampling may have caused measurement bias. Moreover, some studies used self-reported symptoms as the sole criteria without clinical confirmation, which may have resulted in an overestimation of prevalence. Lastly, the representation of different regions was not even, since the majority of the data came from the central and western provinces, which limits the universality of the findings to the whole Saudi population.

15.Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed a considerable prevalence of RLS in Saudi Arabia, with particularly high rates among pregnant women, students, and individuals with chronic medical conditions. These findings call for efforts for improved awareness, early detection, and appropriate management of RLS, especially within primary care and obstetric settings. Addressing modifiable contributors such as iron and vitamin D deficiencies, diabetes, and renal disease may help mitigate disease burden and improve patient well-being. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are warranted to elucidate underlying mechanisms, explore regional variations, and evaluate targeted preventive and therapeutic strategies in highrisk populations.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: None

Acknowledgements: None

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.