Idiopathic Rapidly Deteriorating Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) Presenting as Fulminant Hepatic Failure in a Young Adult: A Diagnostic Challenge.

Abdulmajeed Albalawi¹*, Wahbi Ibrahim Alnazawi², Maitha Althawy³, Reham Alzahrani⁴, Amnah Alharbi⁵, Sarah Abdullah Alharby⁶, Rimas Alqarni⁷, Hala Alhussein⁸, Hasna Albalawi⁹

Full Text

Background: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome resulting from uncontrolled activation of cytotoxic T cells and macrophages. It often mimics sepsis, severe viral infections, or autoimmune hepatitis, leading to delayed diagnosis. While primary HLH arises from genetic defects in cytotoxic function and typically manifests in childhood, most adult cases are secondary, triggered by infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease. Acute liver failure (ALF) as the predominant presentation of HLH is rare and diagnostically challenging, particularly when no clear trigger is identified.

Case summary: We describe a 24-year-old previously healthy Saudi woman with no significant past medical history, who presented with a monthlong history of fever, jaundice, dark urine, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Laboratory evaluation revealed acute fulminant liver failure with coagulopathy, bicytopenia (Hb 9.0 g/dL, platelets 54 × 10⁹/L), and extreme hyperferritinemia (>33,511 µg/L).Despite extensive evaluation, infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes were excluded. Her neurological status deteriorated, with EEG showing subclinical status epilepticus, requiring ICU admission and intubation. The H-Score was 259, indicating >99% probability of HLH, and bone marrow biopsy confirmed hemophagocytosis. She was treated with Emapalumab (anti–IFN-γ), intravenous immunoglobulin, and corticosteroids. Despite therapy, her condition progressed to multiorgan failure, and she died after 22 days of admission.

Conclusion: This case illustrates an unusual presentation of secondary HLH manifesting as acute liver failure, without an identifiable trigger. We highlight the importance of early consideration of HLH in adults with unexplained ALF and hyperferritinemia, as delayed diagnosis may preclude life-saving immunotherapy.

1. Introduction Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, life-threatening syndrome of uncontrolled immune activation driven by excessive cytokine release [1,2]. It manifests with fever, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, and hyperferritinemia, and often mimics severe sepsis, autoimmune flares, or acute liver failure (ALF). While primary HLH results from genetic defects in cytotoxic lymphocyte function and typically presents in childhood, the majority of adult cases are secondary HLH, triggered by infections, malignancies, or autoimmune disease [3,4].

Liver involvement is not uncommon in HLH, yet true fulminant hepatic failure as the dominant presentation is unique and poses major diagnostic challenges [5,6]. The clinical and biochemical overlap between ALF and HLH is significant; fever, transaminitis, coagulopathy, and multiorgan dysfunction are the main features of both. This overlap challenges timely diagnosis needed in such cases. Early identification of HLH in adults with unexplained ALF is therefore crucial, as timely initiation of immunomodulatory therapy may improve outcomes. We present a unique and rapidly fatal case of secondary HLH in a previously healthy young woman who initially presented with acute fulminant liver failure and subclinical status epilepticus, without an identifiable infectious or malignant trigger. This case highlights the diagnostic difficulty of HLH in the setting of ALF of unknown etiology and the importance of considering HLH early, guided by hyperferritinemia and the H-Score.

2. Case Presentation A 24-year-old Saudi female with no significant past medical history, obese (body mass index (BMI) 36.6 kg/m²), was transferred to our tertiary center King Abdulaziz Medical City on 4 August 2024 from King Saud Medical City, where she had been admitted for two weeks for evaluation of progressive jaundice. Her illness had begun over a month earlier, with intermittent fever, dark urine, and yellowish discoloration of the eyes and skin, associated with right upper quadrant abdominal pain that was dull, persistent, and gradually worsening. She reported recurrent episodes of jaundice over the preceding year but had not sought medical attention previously. She denied nausea, vomiting, alcohol or drug use, recent travel, or contact with sick individuals.

Her vital signs on admission revealed low-grade fever (37.9 °C) and tachycardia (115 bpm). She appeared ill and deeply jaundiced. Neurologically, she was conscious but confused (Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 14), with asymmetric motor responses, suggesting a metabolic or systemic encephalopathic process. The abdomen was lax, non-tender, without ascites or organomegaly. There was no rash, edema, or lymphadenopathy.

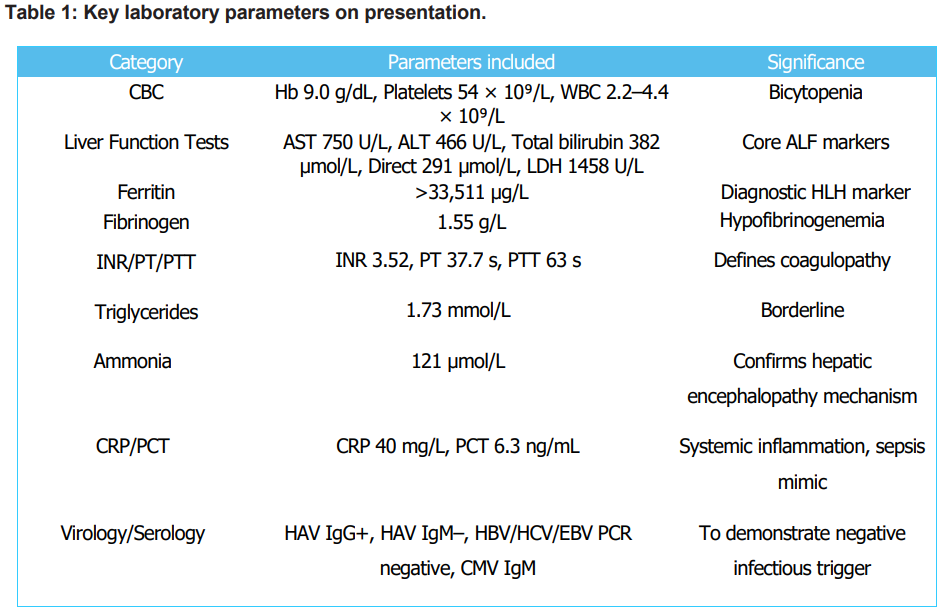

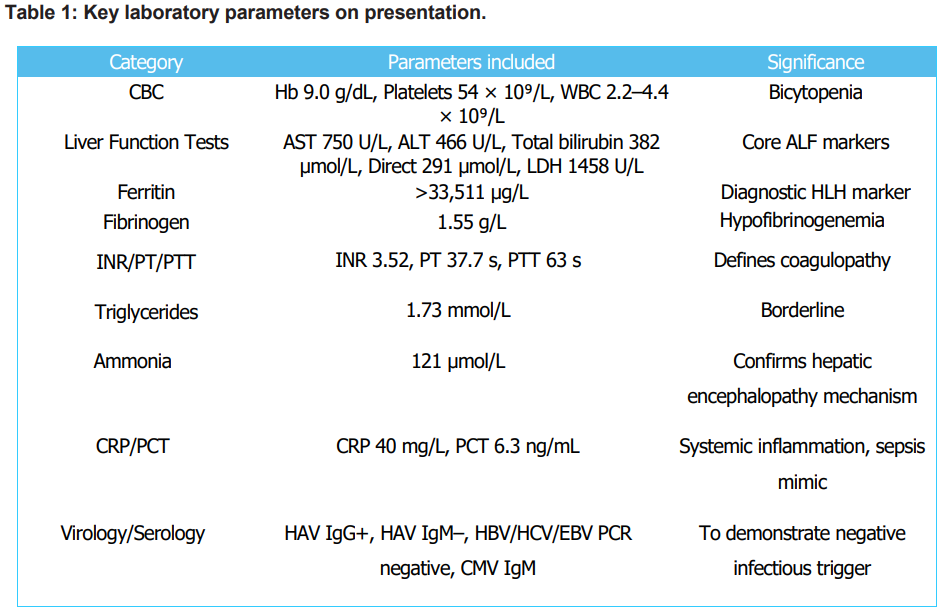

The initial impression was ALF secondary to viral, toxic, or autoimmune etiology, complicated by hepatic encephalopathy (Grade II). An extensive workup, including comprehensive viral serologies (Hepatitis A, B, C, CMV, EBV PCR), autoimmune markers, and toxicological screens, yielded negative results. Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics (Meropenem, Vancomycin) and Antipseudomonal regimen were initiated. Initial laboratory investigations (Table 1) showed bicytopenia (Hb 9.0 g/dL, platelets 54 × 10⁹/L), marked transaminitis (AST 750 U/L, ALT 466 U/L), severe hyperbilirubinemia (total 382 µmol/L, direct 291 µmol/L), profound hyperferritinemia (>33,511 µg/L), hypofibrinogenemia (1.55 g/L), and coagulopathy (INR 3.52), consistent with acute fulminant liver failure (ALF). Inflammatory markers were elevated (CRP 40 mg/L, PCT 6.3 ng/mL). Viral (HAV, HBV, HCV, EBV, CMV PCR), autoimmune, and metabolic workups were negative.

Abbreviations: ALF, acute liver failure, ALT, alanine aminotransferase, AST, aspartate aminotransferase, B12, vitamin B12, CBC, complete blood count, CK, creatine kinase, CMV, cytomegalovirus, CRP, Creactive protein, EBV, Epstein-Barr virus, Hb, hemoglobin, HAV, hepatitis A virus, HBV, hepatitis B virus, HCV, hepatitis C virus, HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, INR, international normalized ratio, LDH, lactate dehydrogenase, PCT, procalcitonin, PCR, polymerase chain reaction, PT, prothrombin time, PTT, partial thromboplastin time, UIBC, unsaturated iron-binding capacity, WBC, white blood cell.

Empiric Meropenem and Vancomycin were continued, with lactulose and rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy management. Despite supportive care, the patient’s neurological status deteriorated. EEG revealed subclinical status epilepticus lasting two hours, for which she was loaded with levetiracetam (4,500 mg) and started on maintenance therapy. repeat EEG showed diffuse encephalopathy with She was intubated and transferred to the ICU, where triphasic waves. MRI brain demonstrated nonspecific parietal white matter signal changes, consistent with metabolic or inflammatory injury.

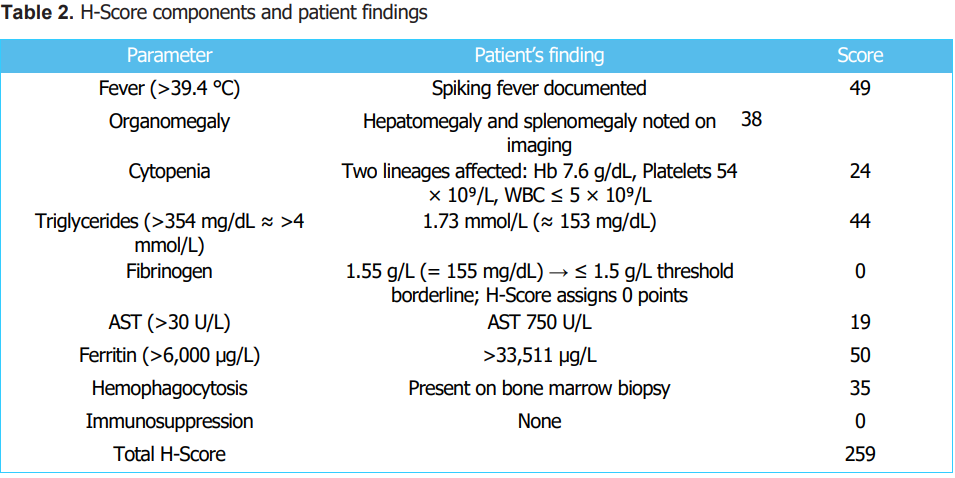

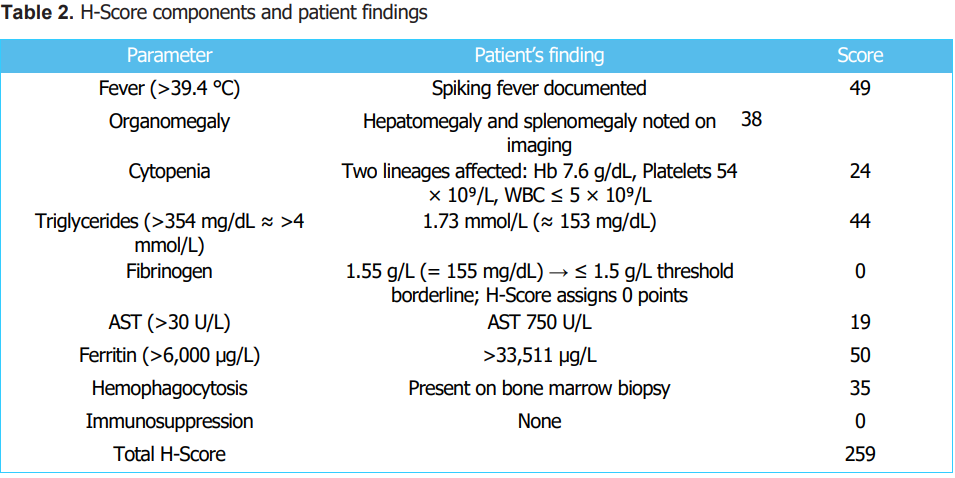

Given the persistent fever, cytopenias, and extreme hyperferritinemia, Hematology consultation was sought to evaluate for Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). The patient meets at least 6 out of the 8 HLH-2004 criteria [7]. Using maximal values, the H-Score was 259, indicating a high probability of secondary HLH (Table 2) [8]. A liver biopsy, performed to elucidate the cause of ALF, revealed giant cell hepatitis without evidence of histiocytosis. In contrast, the bone marrow biopsy (11 August 2024) showed histiocytic proliferation with marked hemophagocytic activity, confirming secondary HLH. Infectious and malignancy screens remained negative, suggesting idiopathic or infection-triggered secondary HLH.

Abbreviations: ALF, acute liver failure; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Hb, hemoglobin; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; WBC, white blood cell count; Plt, platelets; µg/L, micrograms per liter; g/dL, grams per deciliter; g/L, grams per liter; U/L, units per liter; mmol/L, millimoles per liter; mg/dL, milligrams per deciliter; °C, degrees Celsius.

Targeted HLH therapy was initiated promptly with Emapalumab (anti–interferon-γ monoclonal antibody, 350 mg), three days of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and methylprednisolone (40 mg IV for 3 days). The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 32, fulfilling King’s College criteria for potential liver transplantation. However, the Transplant Hepatology team deferred immediate transplantation due to the high risk of HLH recurrence post-LTX, opting to observe the response to immunotherapy. Despite aggressive management, the patient’s condition continued to decline. She developed worsening hepatic encephalopathy, progressive multiorgan dysfunction, and ultimately succumbed on 26 August 2024, eighteen days after initiation of HLHdirected therapy.

3. DISCUSSION Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) represents one of the most diagnostically challenging hyperinflammatory syndromes. The condition’s heterogeneous manifestations, ranging from persistent fever to fulminant multiorgan failure, often mimic severe sepsis, viral hepatitis, or autoimmune hepatitis, resulting in delayed diagnosis and poor outcomes. Our case illustrates this diagnostic challenge, where the initial presentation of ALF and subclinical status epilepticus masked the underlying HLH, and exhaustive evaluation failed to identify an infectious, malignant, or autoimmune trigger.

Secondary HLH in adults is frequently caused by infections, malignancies, or autoimmune diseases, with the virus Epstein-Barr (EBV) being the most common infectious agent [9]. Hepatitis A, B, and C viruses, cytomegalovirus (CMV), HIV, leishmaniasis, mycoplasma, and SARS-CoV-2 infections are among other infectious triggers reported [10,11]. HLH due to malignancy is most often seen in hematologic neoplasms like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or T/NK-cell lymphoma, while autoimmune-related HLH, also known as macrophage activation syndrome, is found in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis [12,13].

Despite comprehensive investigation, up to 20–25% of adult HLH cases remain idiopathic, with no identifiable trigger even after extensive diagnostic investigations [14]. Lin et al. (2016) described a similar case of adult-onset trigger-negative HLH presenting as ALF with fatal multiorgan failure, echoing our patient’s clinical course despite early immunotherapy [15]. Such cases are believed to reflect unrecognized immune dysregulation or cryptic genetic predisposition; indeed, nextgeneration sequencing has identified pathogenic variants in HLH-related genes (PRF1, UNC13D, STX11) in up to 14% of adults with secondary HLH [16,17]. Unfortunately, such testing was not available for our patient.

Adult HLH presenting primarily as ALF is exceptionally rare. Schneier et al. (2015) reported three female adults (aged 44–53) presenting to a transplant center with fulminant hepatic failure later diagnosed as HLH; despite chemotherapy, all patients died, underscoring the poor prognosis associated with delayed recognition [18]. Coppola et al. (2021) similarly described a 74-year-old man with ALF secondary to HLH triggered by diffuse large Bcell lymphoma, who succumbed despite initiation of etoposide-based therapy [19]. More recently, Sequeira et al. (2023) reported HLH with severe acute liver injury in a 65-year-old male with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis, likely triggered by COVID-19 vaccination, who recovered with etoposide and corticosteroids [20]. Likewise, Premec et al. (2023) described postvaccination HLH complicated by ALF, highlighting vaccination as an emerging, though rare, immune trigger [11]. In contrast, our patient had no preceding infection, vaccination, or malignancy, making her case a rare example of trigger-negative adult HLH with rapid progression to liver failure and neurological involvement.

Among infection-triggered adult cases, Termsinsuk and Sirisanthiti documented hepatitis A–associated HLH presenting as impending ALF in a 25-year-old, underscoring the diagnostic challenge in distinguishing viral ALF from HLH-induced hepatic injury [21]. Collectively, these reports reinforce that both trigger-positive and trigger-negative HLH can present as fulminant hepatic failure, and outcomes remain poor unless diagnosis is prompt.

Liver injury in HLH is thought to result from cytokinedriven hepatocellular injury rather than direct infiltration by histiocytes. Elevated levels of interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-6 mediate widespread hepatocyte apoptosis and necrosis [5]. Histopathology typically reveals nonspecific findings—sinusoidal dilatation, steatosis, and necrosis—but can occasionally show giant cell transformation, as seen in our case, suggesting immune-mediated hepatocellular remodeling. These changes may precede overt hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, explaining why early marrow biopsies can be nondiagnostic. Cappell et al. (2018) provided a detailed case report and systematic review highlighting that liver failure in HLH may arise primarily from extrahepatic multiorgan dysfunction rather than intrinsic hepatic necrosis [22]. Their analysis emphasized that liver transplantation should be considered cautiously, as HLH-related ALF often reflects systemic disease severity rather than isolated hepatic injury.

Neurological involvement in HLH, reported in up to 70% of adult cases, ranges from confusion to seizures and coma. Our patient’s subclinical status epilepticus, detected only through EEG, underscores the value of early neurophysiologic assessment. CNS-HLH portends poor prognosis and reflects the extent of cytokine-mediated endothelial and glial injury [23].

The H-Score proved invaluable in our case, rapidly quantifying the likelihood of HLH (>99% probability) and prompting bone marrow biopsy despite the absence of an identifiable trigger.

In adults presenting with ALF and extreme hyperferritinemia (>10,000 µg/L), early use of the H-Score should be considered a diagnostic reflex, expediting hematologic confirmation and immunomodulatory therapy before irreversible hepatic failure ensues [24].

Therapeutic decisions in HLH-associated ALF are complex. Standard regimens (HLH-94/2004 protocols with dexamethasone, etoposide, and cyclosporine) are hepatotoxic, and many adult patients cannot tolerate them. In our patient, treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, IVIG, and Emapalumab (anti–IFN-γ monoclonal antibody) was initiated promptly. Emapalumab, though primarily approved for pediatric refractory HLH, is emerging as a steroid-sparing option in adults, targeting the cytokine axis central to hepatocellular injury. Liver transplantation during active HLH remains controversial due to high recurrence risk. Previous reports, including those of Schneier et al. and Lin et al., documented fatal post-transplant outcomes, supporting our decision to prioritize immune control over transplantation [15,18].

The main teaching points from the case can be drawn together as follows: HLH must always be taken into consideration in the case of ALF of an unknown cause, especially when accompanied by fever, cytopenia, and very high levels of ferritin. Trigger-negative HLH is a particular group that may demonstrate underlying genetic predisposition or immune system disorder. The H-Score has become an important rapid diagnostic tool in critically ill adults with ALF, making it possible for early detection and treatment. Central nervous system monitoring through EEG and MRI must be done without delay to discover the presence of neuroHLH, which can drastically affect the prognosis. At last, it is crucial for the early involvement of hepatology, hematology, and ICU teams working together in a multidisciplinary manner to ensure the correct diagnosis, offer immunomodulatory therapy, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

4. CONCLUSION Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults is a rare but potentially fatal condition that can present as acute liver failure (ALF). It should be suspected in patients with idiopathic ALF, particularly in those exhibiting persistent fever and markedly elevated ferritin levels. Despite the absence of any identifiable infection or malignancy, the case was classified as secondary HLH (triggernegative), with a possible underlying genetic predisposition that was not confirmed. These cases require multidisciplinary coordination among hepatology, hematology, and intensive care teams. Early use of diagnostic tools such as the H-Score and bone marrow biopsy facilitates timely therapeutic intervention. This case underscores the importance of heightened clinicians’ awareness to enable early diagnosis, prompt management, and reduction of acute complications.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Funding: None

Acknowledgements: None

Patient Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s brother for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Ethics Approval: All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability: All relevant data supporting the findings of this report are included within the article. Additional anonymized information can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.