Impact of gender and age on the risk and clinical characteristics of thyroid cancer: A Retrospective Study at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah

1. Introduction Thyroid cancer is a significant health concern and is the most common malignancy arising from hormoneproducing glands (1). Although most thyroid lesions are benign, malignant thyroid tumours—including papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic carcinomas—remain clinically important and may present with neck swelling or thyroid nodules (2). Accurate diagnostic evaluation is therefore essential, and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is widely used to support timely assessment and management (3).

Globally, thyroid cancer incidence has increased over recent decades, with marked geographic variation and consistent differences by sex and age (4). Thyroid cancer–specific mortality has also been reported to increase in some populations, with greater rises among men and in patients with larger tumours (2–4 cm) (5). Multiple risk factors have been proposed—including genetic susceptibility, iodine intake, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, autoimmune thyroid disease, obesity, and environmental or lifestyle factors—yet many of these are not routinely or consistently captured in retrospective hospital-based datasets, which typically emphasize measurable demographic and clinicopathologic variables (6).

In Saudi Arabia, thyroid cancer incidence has increased notably over time, underscoring the importance of defining local epidemiology and clinicopathologic patterns (7,8). Prior reports indicate higher incidence among females and a substantial increase among males, highlighting the need for increased awareness and timely diagnosis in both sexes (8). Studies from Saudi Arabia also suggest that thyroid cancer may be diagnosed at a younger age and with larger tumour size compared with some other settings, with limited evidence of a trend toward smaller tumours over time (9).

In addition, thyroid cancer has been associated with quality-of-life impairment and symptom burden in local populations (10). Despite this growing burden, important gaps remain in understanding how age and sex relate to tumour characteristics and key clinical outcomes in specific Saudi populations, including patients in Jeddah.

Therefore, this retrospective study aimed to evaluate the association of age and sex with thyroid cancer clinicopathologic features and outcomes among adult patients with confirmed thyroid cancer diagnosed and/or treated at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, between January 2010 and December 2023. The study focused on variables captured in the medical record, including histologic type, tumour size, stage, lymph node metastasis, invasion of adjacent structures, documented distant metastasis, treatment and response, and recurrence.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Study design and setting: This retrospective medical record review was conducted at King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and was reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for observational studies. The study period extended from January 2010 through December 2023.

Study population and eligibility: We included all adult patients (≥18 years) with confirmed thyroid cancer who were diagnosed and/or treated at KAUH during the study period. Patients aged <18 years were excluded. The presence of other malignancies, when documented in the medical record, was extracted and analyzed as a study variable. All consecutive eligible cases available in the hospital records were included; therefore, no formal sample size calculation was performed.

Data collection and variables: Patient demographic and clinical data were extracted from electronic and paper medical records. Data were recorded using a standardized data collection form and subsequently organized in a spreadsheet for analysis. Variables collected included sex, age at diagnosis, histologic type, tumour size, lymph node metastasis, invasion of adjacent structures, documented distant metastasis, AJCC/TNM stage, diagnostic method, family history of thyroid cancer, treatment modality, response to treatment, recurrence, prior thyroid-related conditions or abnormalities, prior thyroid-related screenings or tests, presence of other cancers, other endocrine disorders, number of affected lymph nodes (where applicable), and follow-up duration.

Statistical analysis: Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS (version 26). Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were compared using the independentsamples t-test (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (three or more groups), as appropriate. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval and confidentiality: Ethical approval was obtained from the Unit of Biomedical Ethics, Research Ethics Committee (REC), Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Reference No. 140-24). Patient identifiers were not collected. To ensure confidentiality, records were anonymized and stored securely with access restricted to the research team. As this was a retrospective review using de-identified data, informed consent was waived in accordance with institutional policy.

3. RESULTS:

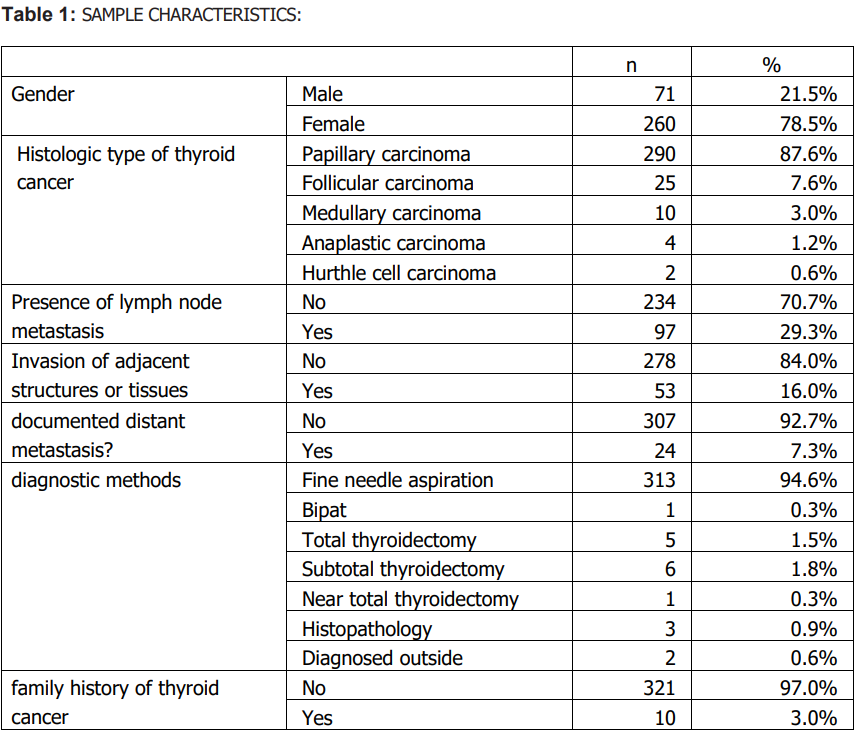

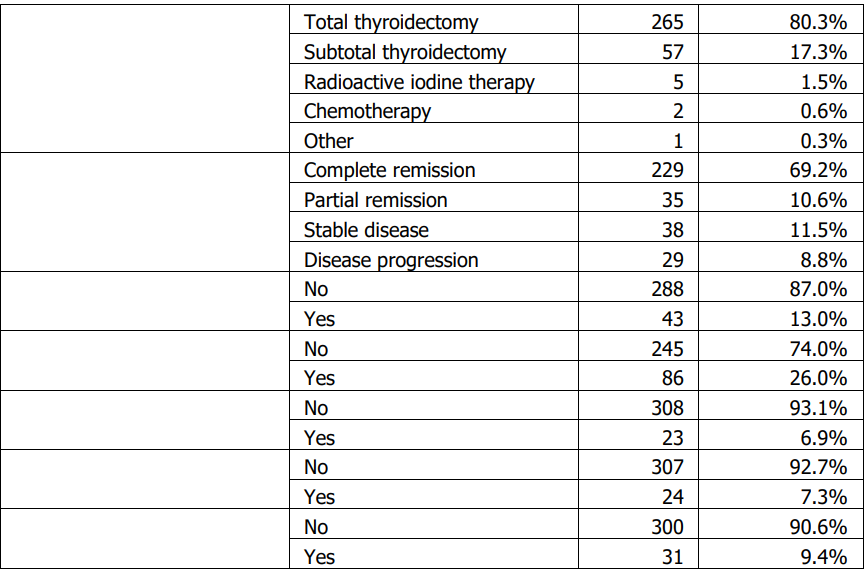

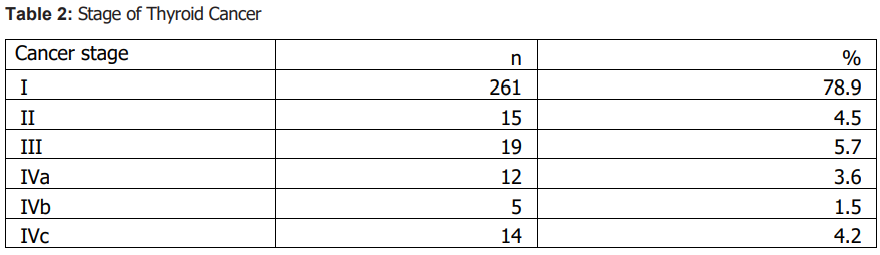

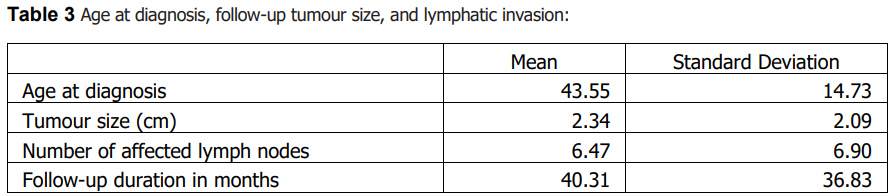

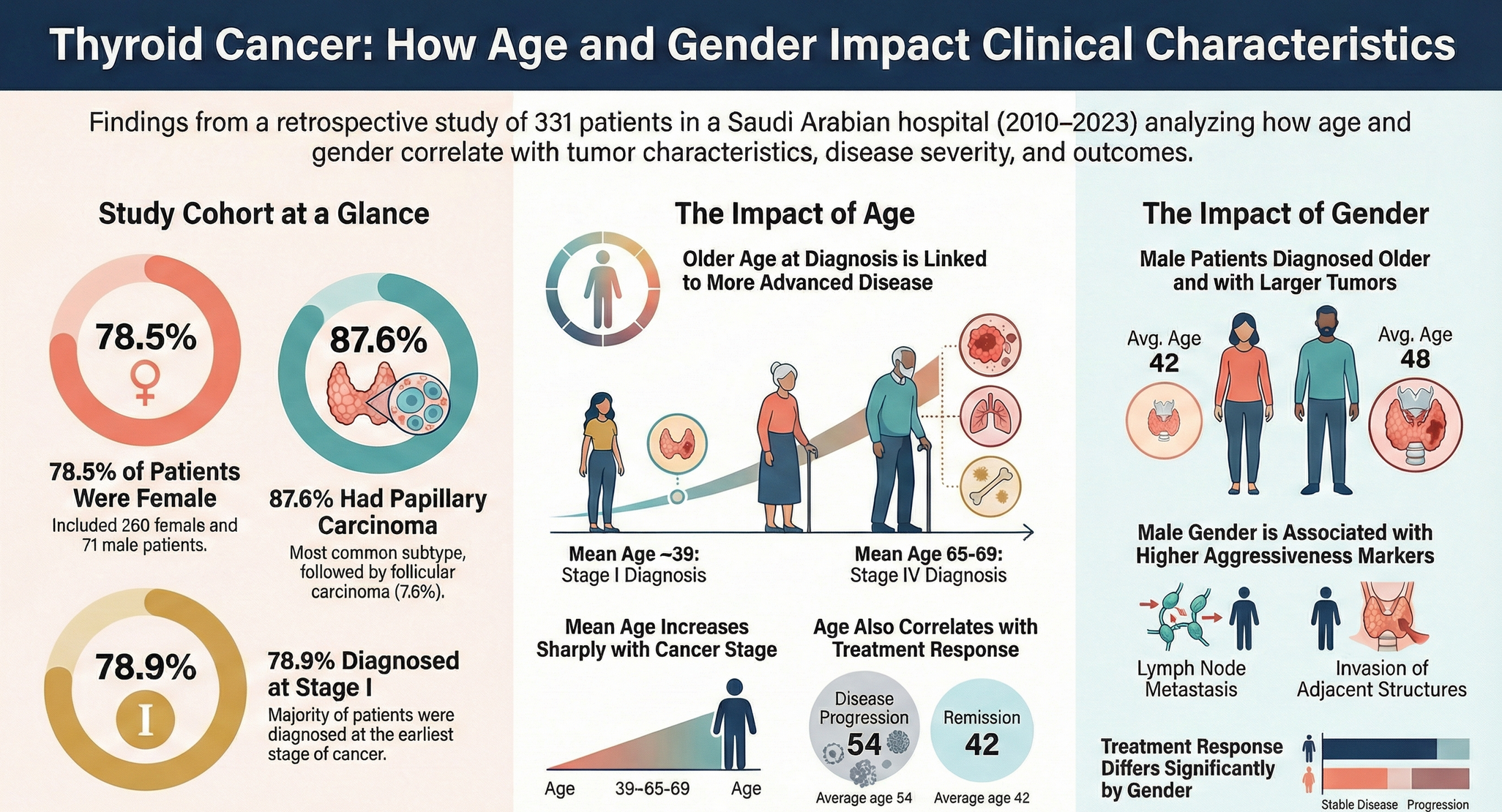

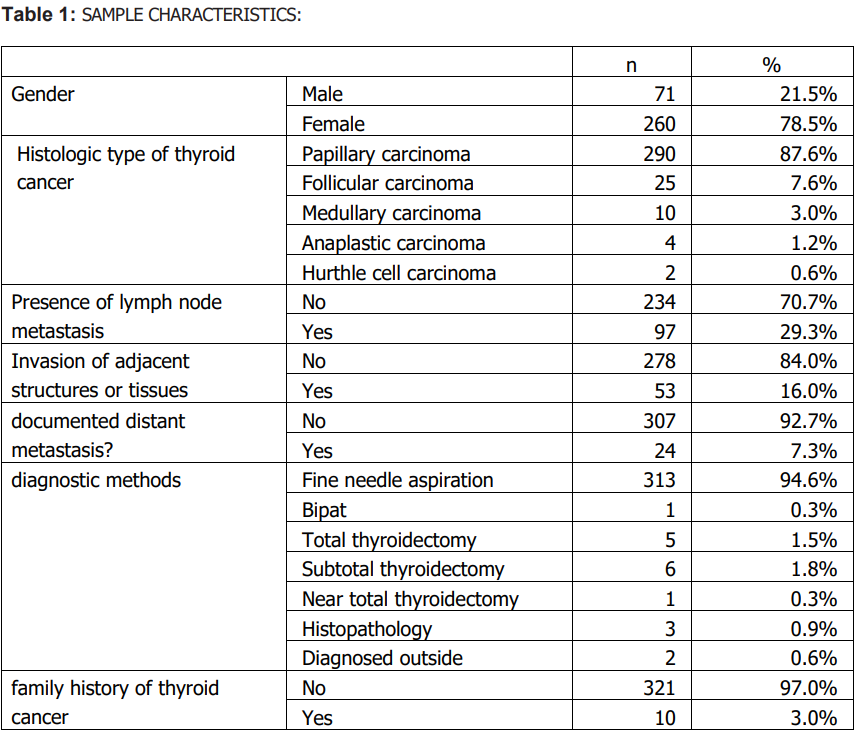

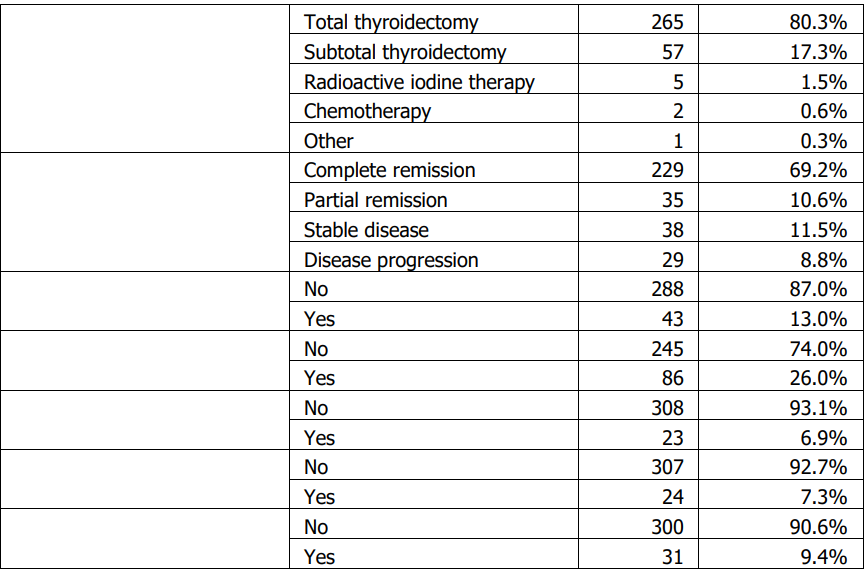

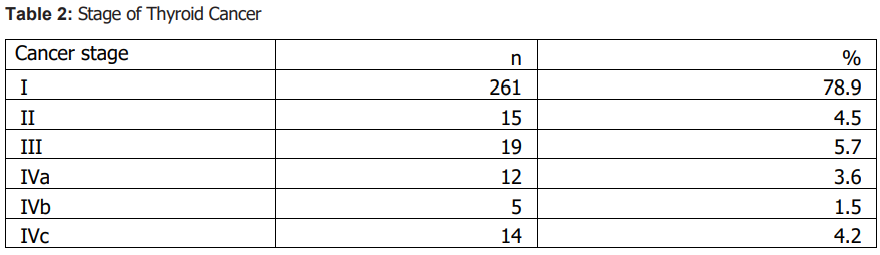

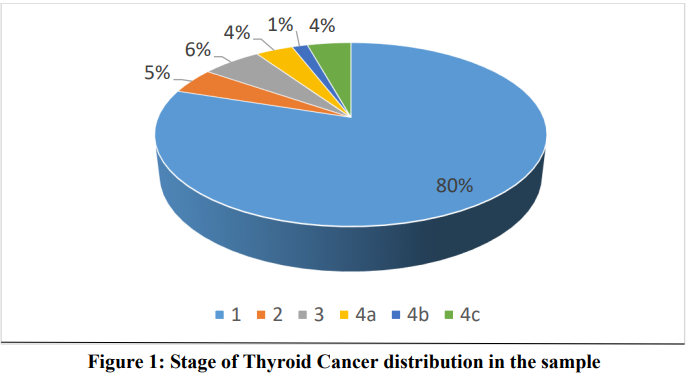

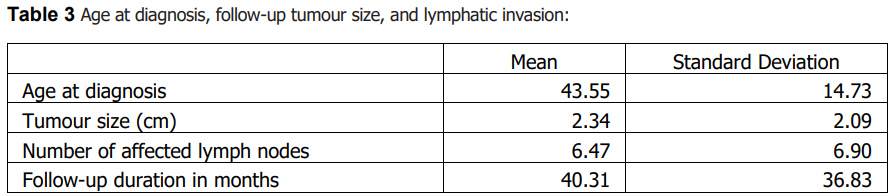

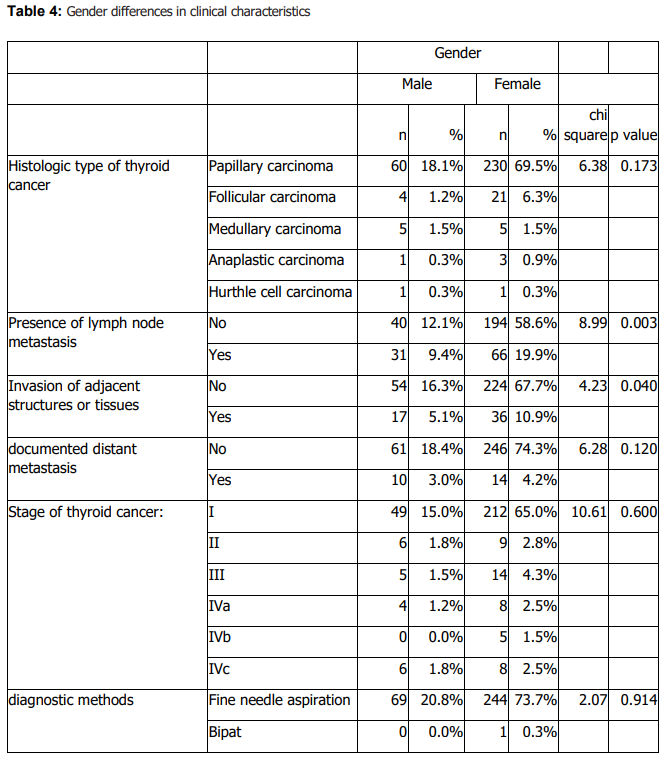

Sample characteristics A total of 331 patients with thyroid cancer were included; 71 (21.5%) were male and 260 (78.5%) were female. Papillary carcinoma was the predominant histologic subtype (87.6%, n=290), followed by follicular (7.6%, n=25), medullary (3.0%, n=10), anaplastic (1.2%, n=4), and Hürthle cell carcinoma (0.6%, n=2). Lymph node metastasis was documented in 29.3% (n=97), invasion of adjacent structures in 16.0% (n=53), and distant metastasis in 7.3% (n=24). Most patients were diagnosed at stage I (78.9%, n=261). Summary descriptive statistics are presented in Tables 1–3.

Gender differences

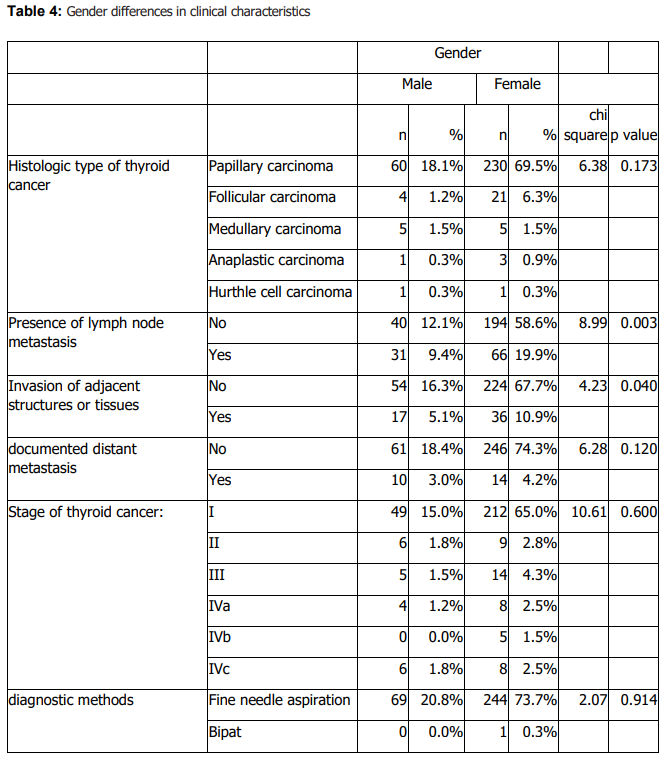

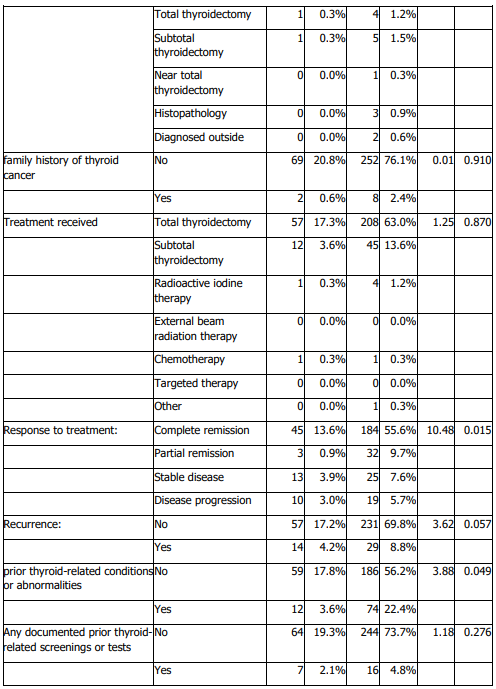

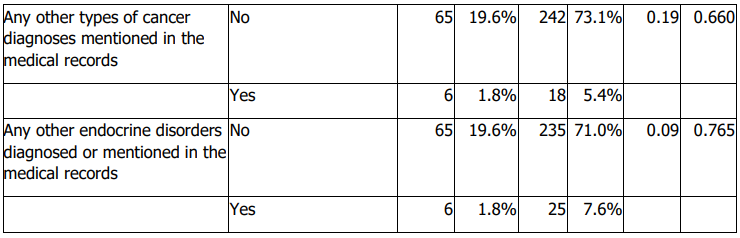

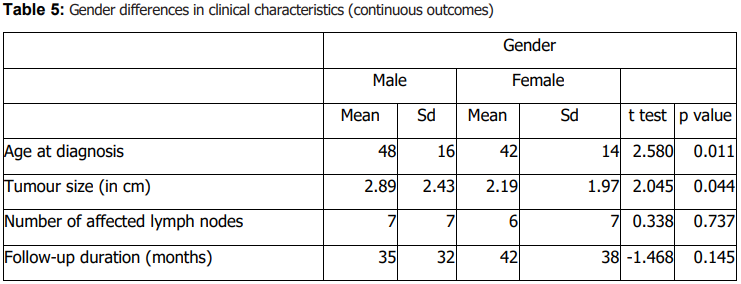

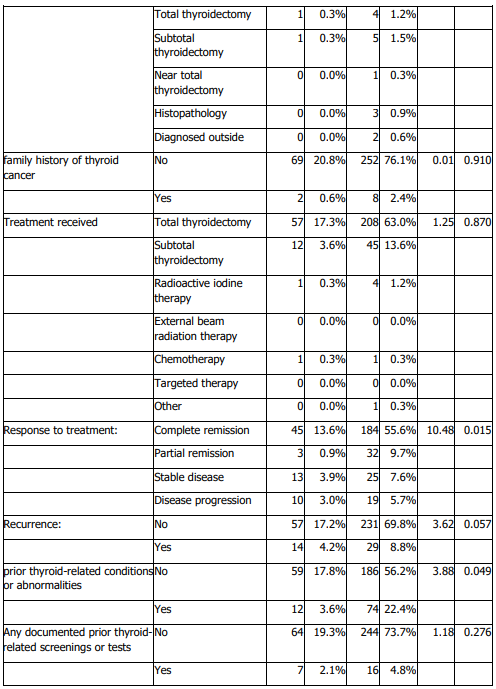

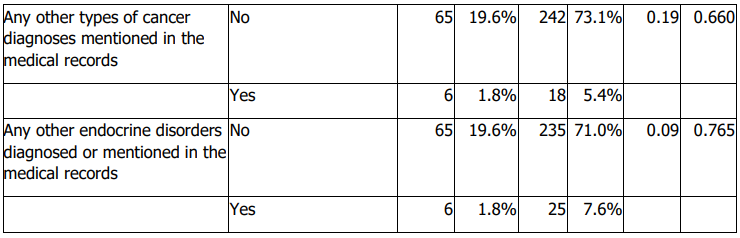

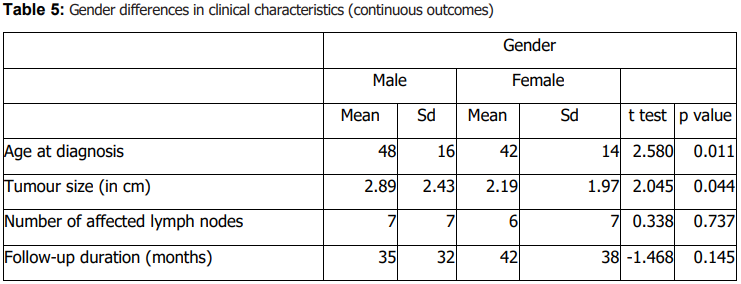

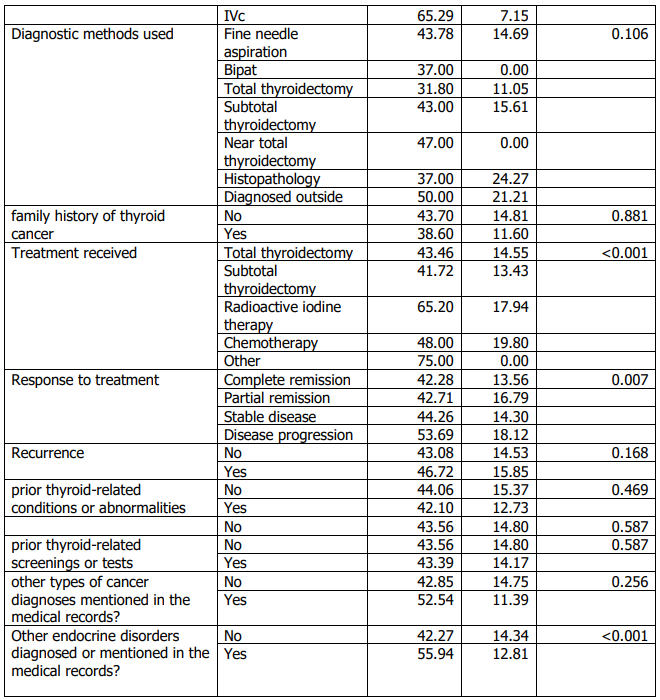

Histologic subtype distribution did not differ significantly by sex (Table 4). Lymph node metastasis and invasion of adjacent structures differed significantly by sex (Table 4). Males were older at diagnosis and had larger tumours than females (Table 5). Treatment response also differed by sex (Table 4). No significant sex differences were observed in stage, diagnostic method, family history of thyroid cancer, documented distant metastasis, recurrence, other cancer diagnoses, or other endocrine disorders (Table 4).

Age at diagnosis and tumour aggressiveness /outcomes

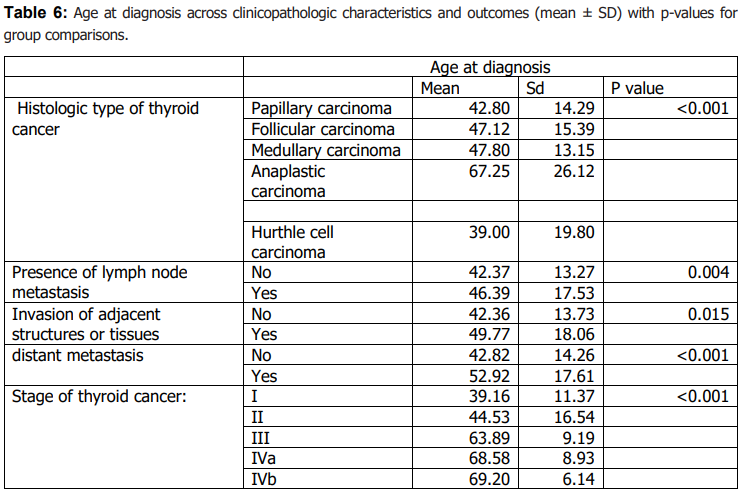

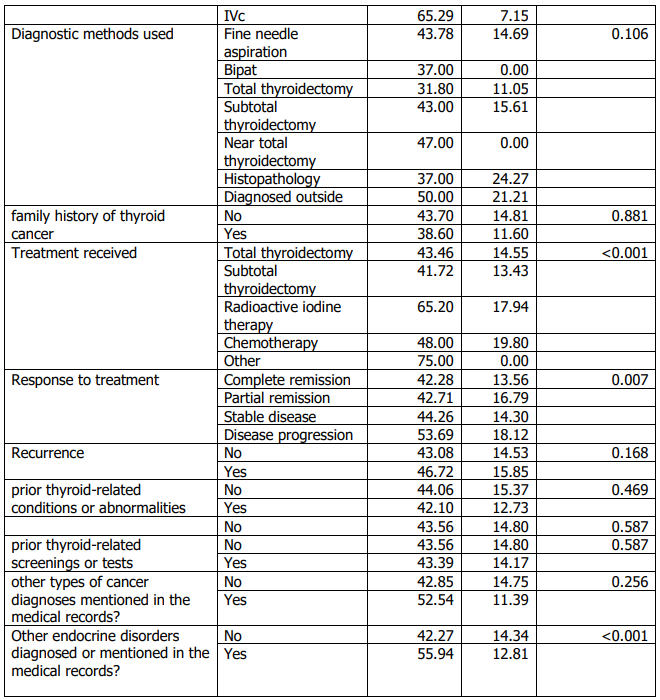

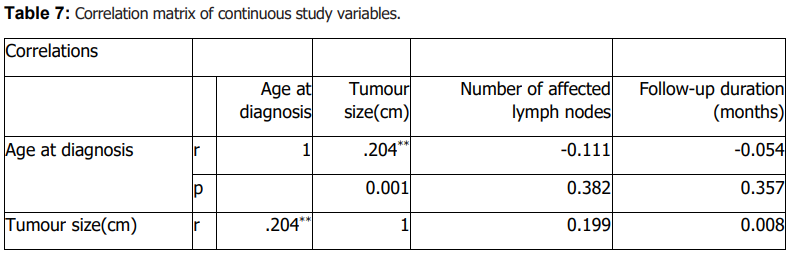

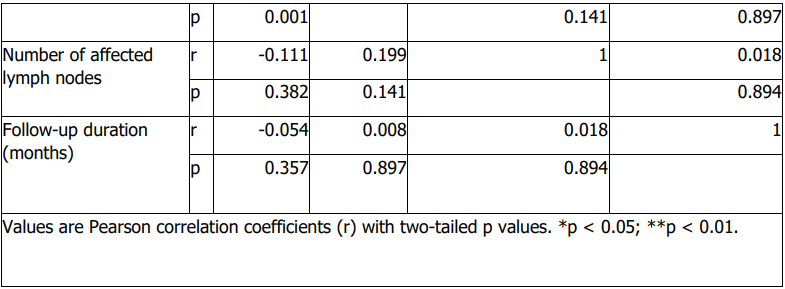

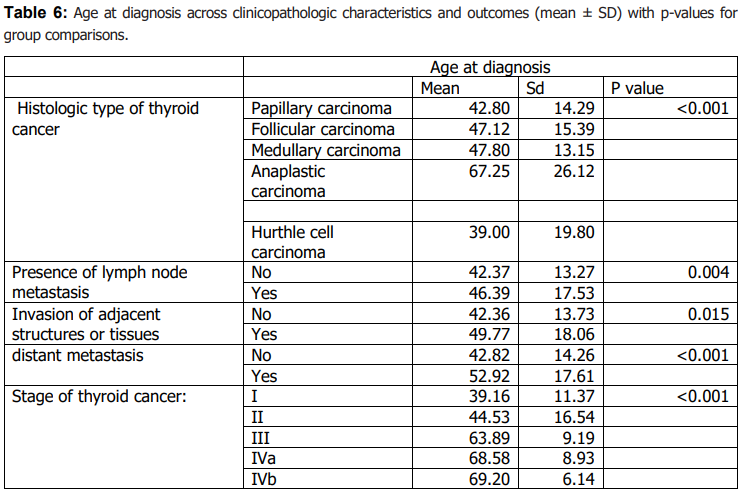

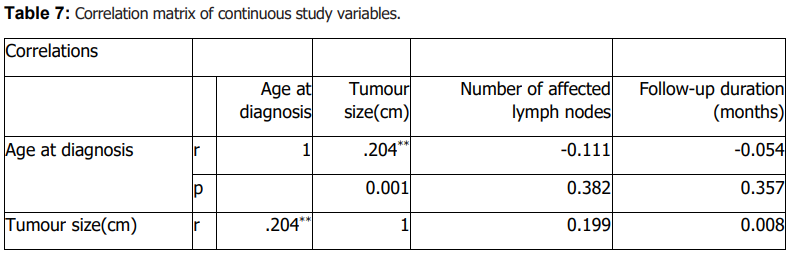

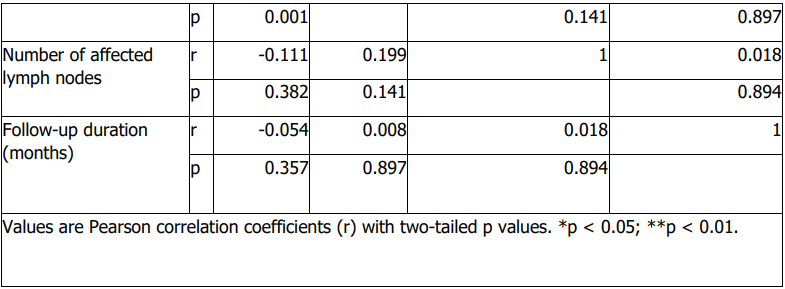

Age at diagnosis differed significantly across histologic subtypes (Table 6). Older age at diagnosis was significantly associated with markers of more advanced disease, including higher stage, invasion of adjacent structures, and documented distant metastasis (Table 6). Age at diagnosis was also associated with lymph node metastasis (Table 6). Tumour size showed a modest positive correlation with age at diagnosis (Table 7), while follow-up duration and the number of affected lymph nodes were not significantly correlated with age or tumour size (Table 7).

4. Discussion Thyroid cancer in this retrospective cohort from King Abdulaziz University Hospital was diagnosed predominantly in women, and papillary carcinoma accounted for the large majority of cases. This overall pattern aligns with international and regional reports describing higher diagnosed incidence among females and a predominance of differentiated (particularly papillary) thyroid carcinoma (14,16,21). The female predominance in diagnosed cases is consistently observed across studies and is commonly attributed to a combination of biological and healthcare-related factors; however, these underlying drivers were not directly measurable in our dataset and therefore cannot be evaluated in this analysis (16,17). Within Saudi Arabia, rising incidence and variation by sex and region have been reported, underscoring the relevance of institution-based studies that characterize clinicopathologic patterns in specific local populations (7,8,14).

Beyond distribution, our findings support the clinical relevance of sex and age as correlates of tumour characteristics and outcomes. In sex-stratified comparisons, males were older at diagnosis and had larger tumours than females, consistent with prior literature suggesting that men often present at older ages and may exhibit less favourable tumour features (22,23). We also observed significant sex differences in lymph node metastasis and invasion of adjacent structures on univariable analysis (Table 4), alongside differences in age at diagnosis and tumour size (Table 5). At the same time, published evidence on sex differences in aggressiveness and outcomes is heterogeneous, and differences may reflect case mix, diagnostic intensity, and follow-up practices across settings (31,32). Accordingly, our results should be interpreted as associations within a single-center cohort rather than definitive estimates of sex-based risk.

Age at diagnosis showed a consistent relationship with markers of disease extent. Older patients were more likely to present with advanced stage and were more frequently associated with invasion of adjacent structures and documented distant metastasis; age was also positively associated with tumour size, and these associations were observed in univariable analyses (Table 6–7). These observations align with the well-established prognostic importance of age in thyroid cancer and prior reports linking older age with more advanced disease features (19,20,27–30). We also identified significant associations between age (and sex) and treatment response, although the direction and magnitude of such associations vary across studies, including those from the region (23– 26). Clinically, these findings support maintaining heightened diagnostic and follow-up vigilance for older adults and for groups more likely to present with larger tumours, while recognizing that the present retrospective design does not allow causal inference.

This study has limitations inherent to retrospective, single-center chart reviews. Data completeness depended on existing documentation, and some potentially important covariates were not consistently available or measurable (e.g., detailed risk-factor exposures, standardized treatment protocols over time), which may introduce residual confounding. The cohort was drawn from a teaching/referral hospital, limiting generalizability to the wider community. In addition, follow-up duration varied, which may affect observed outcome frequencies such as recurrence. Despite these limitations, the study provides institutionspecific evidence describing how age and sex relate to tumour characteristics and selected outcomes in a large local cohort, and it highlights areas for future multicenter studies with standardized data capture to validate and extend these findings.

5. Conclusion:

In this retrospective single-center study of adult patients with thyroid cancer diagnosed and/or treated at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah (2010–2023), older age at diagnosis was associated with larger tumours and more advanced disease features, including higher stage, invasion of adjacent structures, and documented distant metastasis. Male patients were diagnosed at an older age and had larger tumours than female patients. In addition, age and sex were associated with treatment response within this cohort. These findings support considering age and sex when interpreting tumour characteristics and planning follow-up, while recognizing that the retrospective design limits causal inference and that multicenter studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Ethical Approval: The study was Approved by the Unit of Biomedical Ethics, Research Ethics Committee (REC), Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Reference No. 140-24). All data were anonymized and handled in accordance with institutional ethical standards.

Patient Consent: Patient consent was waived as the study used deidentified, retrospective data.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study’s conception, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author Approval for Submission: All authors and co-authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript, and its submission has been made with their full knowledge and consent.